What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“This Paper, has been printed with ink manufactured by said Geyer, for several Months past.”

When the Continental Association went into effect, colonizers looked to “domestic manufactures” or goods produced in the colonies as alternatives to imports. The eighth article of that nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation agreement even stated that “we will, on our several Stations, encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts and the Manufactures of this Country.” Henry Christian Geyer did just that in an advertisement that appeared in the January 23, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy. He announced that he “manufactured” printing ink “in large or small Quantities, at his Shop near Liberty-Tree South-End of Boston.” Devoting such “Industry” to the “Manufactures of this Country” testified to Geyer’s support of the American cause; noting the proximity of his shop and such an important symbol underscored his patriotism.

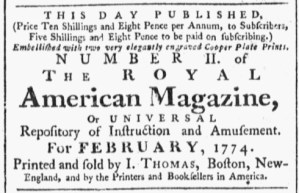

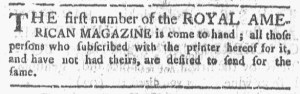

Yet Geyer had more to say about the matter. He proclaimed to “the Public” that “the Royal American Magazine, was not printed with his Ink.” His advertisement gave no indication why he singled out the Royal American Magazine and not any of the newspapers published in Boston or any of the city’s printing offices. After all, if he had captured the entire market (except for the Royal American Magazine) then he had less need to place an advertisement. He chose to shame Joseph Greenleaf, the publisher of the Royal American Magazine, for not purchasing his product, perhaps intending to bully him into buying Geyer’s printing ink or perhaps settling some score by embarrassing him in a public forum.

Geyer’s advertisement concluded with a nota bene that clarified that “This Paper, has been printed with Ink manufactured by said Geyer, for several Months past.” Geyer may have written the nota bene himself, presenting a testimonial of the quality of the ink that readers could assess for themselves as they held the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy in their hands. Alternately, Nathaniel Mills and John Hicks, the printers of the newspaper, could have added the nota beneon their own as a means of demonstrating that they supported domestic manufactures even before the Continental Association went into effect.