Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“N.B. A Negroe woman Cook, healthy honest and sober, 33 years old.”

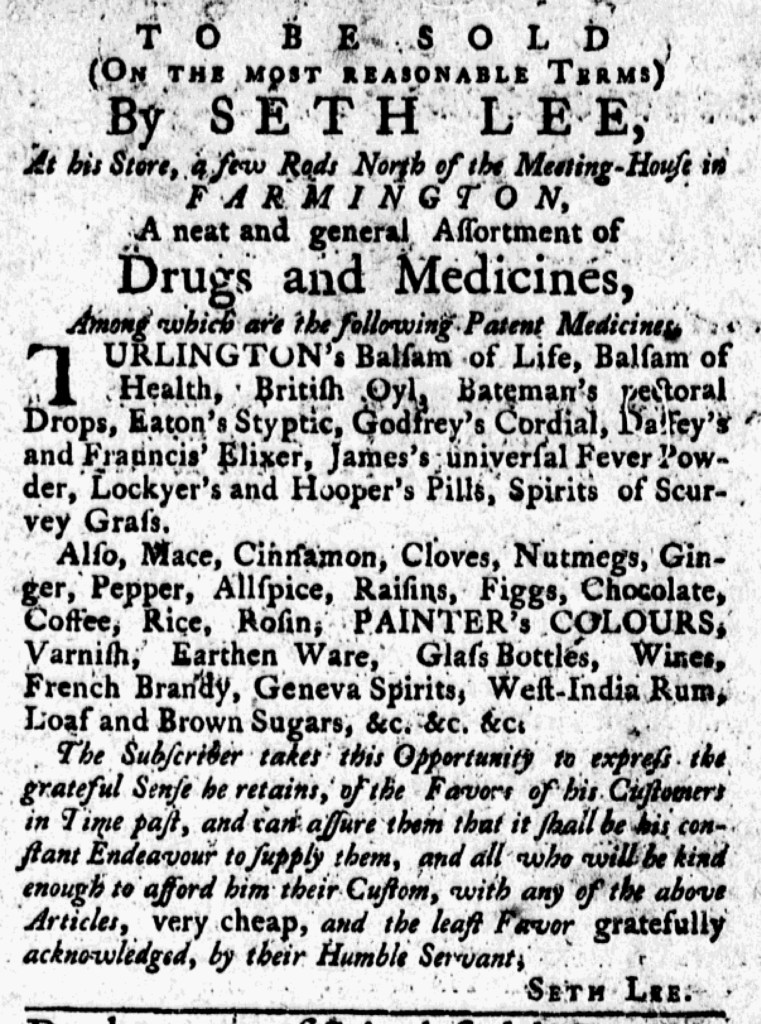

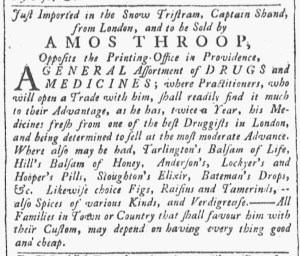

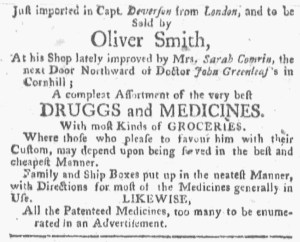

Alexander Stenhouse apparently wished to discontinue his medical supply business in Baltimore. In the final week of December 1775, he placed advertisements in both Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette and the Maryland Journal that listed a “general Collection of DRUGS and MEDICINES” available for sale. He added vials, “Large bottles for Distilled Waters,” “Pill pots of various sizes, labelled and plain,” “Mortars and pestles,” “Surgeons Instruments,” and other medical equipment. He even included “Shop Furniture,” suggesting that he no longer needed it because he would no longer pursue that trade. In addition, he declared that the “Drugs and Medicines will not be sold singly, so it is expected those who want will take an assortment.” To make the offer even more attractive, Stenhouse promised a “considerable discount … to a person who will purchase the whole.” Perhaps Stenhouse even intended to leave Baltimore. His inventory concluded with a “Collection of Books, mostly modern publications,” and “Houshold and kitchen furniture, in general almost new.”

Stenhouse offered more than just the contents of his shop and home for sale. In a nota bene that followed his signature, he described a “Negroe woman Cook, healthy honest and sober, 33 years old.” The sale of that woman whose name was once known testifies to the widespread use of the early American press to perpetuate slavery and the slave trade. At a glance, the phrases “TO BE SOLD” and “DRUGS and MEDICINES,” dominated Stenhouse’s advertisement. The list of items for sale, divided into two columns, unlike any of the other in either newspaper, likely caught readers’ eyes as well. Those aspects of Stenhouse’s advertisement overshadowed but did not eclipse the portion that offered an enslaved woman for sale. The format did not indicate that Stenhouse felt any shame or embarrassment about selling a “Negroe woman Cook” and wanted to downplay it; instead, the format demonstrated just how casually enslavers incorporated such transactions into everyday advertising and routine business. “N.B.” or nota bene, after all, meant “take note.” Stenhouse wished for readers to “take note” that he wished to sell an enslaved woman as he “disposed of” the contents of his shop and home.