What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Those who send Advertisements, are also desired to send the Pay at the same Time.”

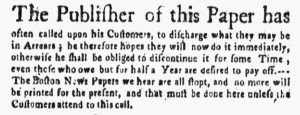

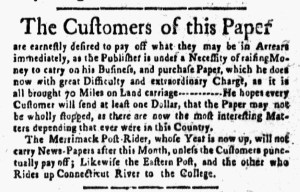

On April 28, 1775, a little over a week after the battles at Lexington and Concord, Daniel Fowle, the printer of the New-Hampshire Gazette placed a notice calling on subscribers and other customers “to discharge what they may be in Arrears” and to do so “immediately, otherwise he shall be obliged to discontinue [the newspaper] for some Time.” He added that all the newspapers published in Boston “are all stopt, and no more will be printed for the present.” Fowle warned, “that must be done here unless the Customers attend to this call.” He could not continue publishing the New-Hampshire Gazette without receiving payments for it.

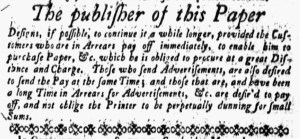

Just two weeks later, he inserted another notice, declaring that he “Designs, if possible, to continue [the newspaper] a while longer, provided the Customers who are in Arrears pay off immediately, to enable him to purchase Paper, &c. which he is obliged to procure at a great Distance and Charge.” This time he singled out advertisers, a cohort of customers that he had not explicitly mentioned in his previous notice. “Those who send Advertisements,” Fowle instructed, “are also desired to send the Pay at the same Time.” Furthermore, “those that are, and have been a long Time in Arrears for Advertisements, &c. are desir’d to pay off, and not oblige the Printer to be perpetually dunning for small Sums.”

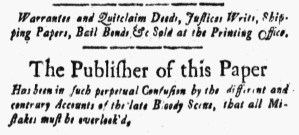

In that notice, Fowle revealed an important aspect of his business practices. Most printers extended credit to subscribers. Fowle certainly did so, prompting his notices in late April and early May 1775, as well as other notices that he frequently inserted in the New-Hampshire Gazette over the years. Many historians of the early American press posit that printers allowed for generous credit for subscriptions, permitting subscribers to avoid paying for years, because they generated significant revenue from advertisements. Doing so, depended on advertisers having confidence in the circulation of newspapers, explaining why printers allowed some subscribers to fall years behind on making payments. Accordingly, printers supposedly required advertisers to pay for their notices when they submitted them for publication.

Fowle’s notice in the May 12, 1775, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette suggests that he did not demand payment before publishing advertisements in his newspaper. The Adverts 250 Project has collected other notices in which printers called on customers to pay for advertisements, though in many cases the use of the word “advertisements” was ambiguous. It could have meant newspapers notices or it could have referred to printing handbills and broadsides (especially for printers who asserted that they could print “advertisements” with only an hour’s notice). In this case, however, it seems clear that Fowle meant newspaper notices when he stated, “Those who send Advertisements, are also desired to send the Pay at the same Time.” Fowle and other printers very well may have adopted practices different from the usual narrative about printers uniformly requiring advertisers to pay in advance.