What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He has been over to London for Improvement.”

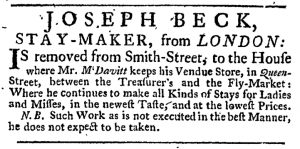

In their advertisements, artisans who had migrated across the Atlantic frequently asserted their origins as part of their attempt to attract customers. For instance, Joseph Beck promoted himself as a “Stay-Maker, from LONDON” in the November 5, 1767, edition of the New-York Gazette: Or, the Weekly Post-Boy. Establishing a connection to London laid the foundation for making other appeals to consumers. It often suggested some sort of specialized training in a trade (and some artisans explicitly noted that they had served out an apprenticeship with a master in London). It also signaled familiarity with the current fashions in the cosmopolitan center of the empire. Artisans sought to allay anxieties that the items they made and sold in the colonies were inferior in quality or taste when compared to the wares available in London.

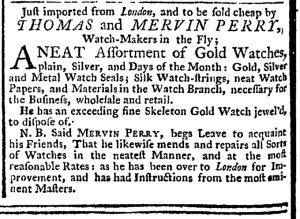

Not all colonial artisans, however, could proclaim that they migrated “from LONDON” in their advertisements. Many had been born and received their training in the colonies. Such was probably the case for Thomas Perry and Mervin Perry, “Watch-Makers in the Fly” in New York. Like many of their competitors in New York and their counterparts in other cities and towns, the Perrys not only made and repaired watches but also imported them from London. Yet they realized they could acquire more cachet among consumers if they established other connections to London. It was not sufficient merely that they acquired their merchandise from London.

To that end, the watchmakers inserted a nota bene that informed potential customers that Marvin Perry had “been over to London for Improvement, and has had Instructions from the most eminent Masters.” Although he did not undertake a complete apprenticeship in London, Perry had supplemented his training and presumably improved his skills. He implied that readers could expect that the “Instructions from the most eminent Masters” improved the quality of Perry’s work. This additional training also confirmed that he performed his work “in the neatest Manner.”