What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

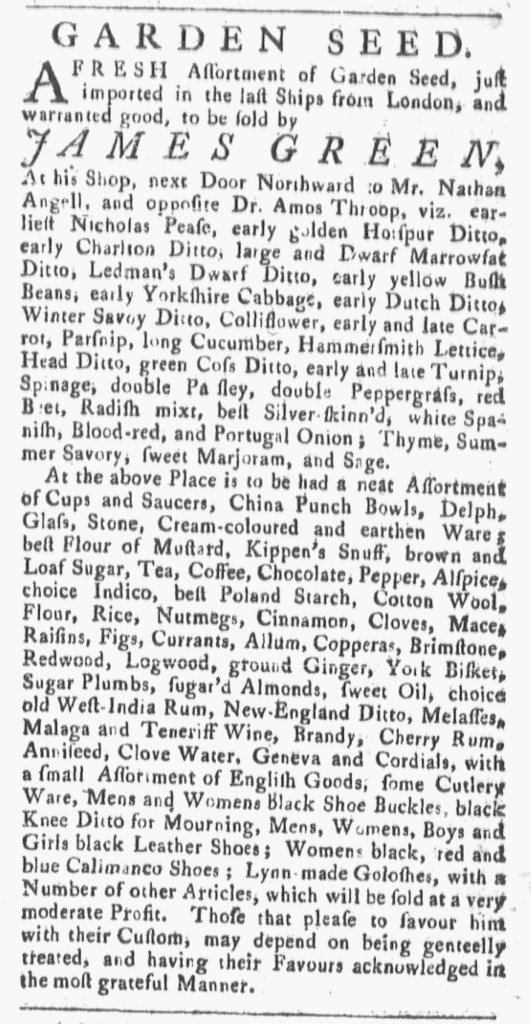

“GARDEN SEED … At the above Place is to be had a neat Assortment of Cups and Saucers.”

In Boston, advertisements for garden seeds continued to fill the pages of newspapers as spring approached in 1773. On March 1, Elizabeth Greenleaf, Ebenezer Oliver, and Susanna Renken placed notices in the Boston Evening-Post, John Adams, Elizabeth Clark and Nowell, Elizabeth Dyar, Elizabeth Greenleaf, Ebenezer Oliver, and Susanna Renken placed notices in the Boston-Gazette, and Elizabeth Greenleaf and Susanna Renken placed notices in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy. On March 4, John Adams, Elizabeth Greenleaf, Ebenezer Oliver, and Susanna Renken ran advertisements in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter and Lydia Dyar, Elizabeth Greenlead, Anna Johnson, and Susanna Renken ran advertisements in the Massachusetts Spy.

Such advertisements did not saturate newspapers published in other towns in New England to the same extent, but they did appear. For instance, Nathan Beers informed residents of New Haven that he sold a “Quantity of GARDEN-SEEDS” in a notice in the Connecticut Journal on March 5. He stated that his seeds were “cultivated according to the rules of the best English Gardiners.” The following day, James Green ran his own advertisement for a “FRESH Assortment of Garden Seed, just imported in the last Ships from London,” in the Providence Gazette. Like other seed sellers, he provided an extensive list of his wares.

Unlike most others, however, Green did not focus exclusively on seeds. He used seasonal merchandise to introduce prospective customers to other goods available at his shop. Indeed, he devoted just more than half the space in his advertisement to a catalog of housewares, groceries, and garments, including “a neat Assortment of Cups and Saucers,” “best Flour of Mustard,” and “Mens, Womens, Boys and Girls black Leather Shoes.” He promised “a Number of other Articles.” To further entice consumers, Green stated that he sold those goods “at a very moderate Profit.” In other words, he did not mark up the retail prices extravagantly but instead offered good bargains for his customers.

Eighteenth-century advertisers frequently described their merchandise as “suitable for the season.” Sometimes they used headlines with similar sentiments, such as “WINTER GOODS” in a notice Frazier and Geyer ran in the March 1 edition of the Boston Evening-Post. In contrast, Green experimented with another marketing strategy. He focused one particular season item, garden seeds, in the first portion of his advertisement and then directed attention to the rest of his inventory after capturing the attention of prospective customers.