What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Be very punctual in their Publications … and be particularly careful in circulating the Papers.”

The first page of the April 2, 1772, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette consisted almost entirely of the masthead and advertisements placed by colonizers. At the top of the first column, however, Peter Timothy, the printer, inserted his own notice before the “New Advertisements” placed by his customers. In it, he announced that “my present State of Health will not admit of my continuing the PRINTING BUSINESS any longer.” Effective on May 1, “Thomas Powell, Edward Hughes, & Co.” would “conduct and continue the Publication of this GAZETTE.” Wishing for the success of his successors, Timothy assured readers that they could expect the same quality from the publication under new management that he had delivered “during the Course of Thirty-three Years.” Picking up where he left off, the partners “will have the Advantage of an extensive and well established Correspondence” with printers and others who provided news. In addition, Timothy declared that they would “be very punctual in their Publications—regular and exact in inserting the Prices Current—continue my Marine List—and be particularly careful in circulating the Papers.”

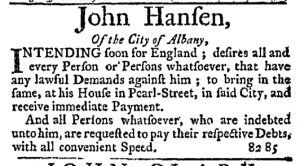

Timothy addressed subscribers and other readers when he mentioned the “Charles-Town Price Current” and “Timothy’s Marine List,” as the printer called his version of the shipping news obtained from the customs house. In making promises about the punctually publishing newspapers and attending to their circulation, however, he addressed both readers and advertisers. Colonizers who paid to insert notices wanted their information disseminated as quickly and as widely as possible, whether they encouraged consumers to purchase goods and services, invited bidders to attend auctions and estate sales, or offered rewards for the capture and return of enslaved people who liberated themselves. Certainly subscribers wanted their newspapers to arrive quickly and efficiently, but Timothy understood the importance of advertising when it came to generating revenues. After all, he devoted only five of the twelve columns in the April 2 edition to news (including the “Charles-Town Price Current” and “Timothy’s Marine List”) and the other seven to advertising. In addition, he distributed a half sheet supplement, another six columns, that consisted entirely of advertising. Paid notices accounted for just over two-thirds of the content Timothy disseminated on April 2, even taking his “extensive and well established Correspondence” into consideration.

As he prepared to pass the torch to Powell and Hughes, Timothy did not address advertisers directly, but he certainly addressed concerns that would have been important to them. The South-Carolina Gazette competed with two other newspapers published in Charleston at the time. Timothy sought to keep both subscribers and advertisers loyal to the publication he would soon hand over to new partners.