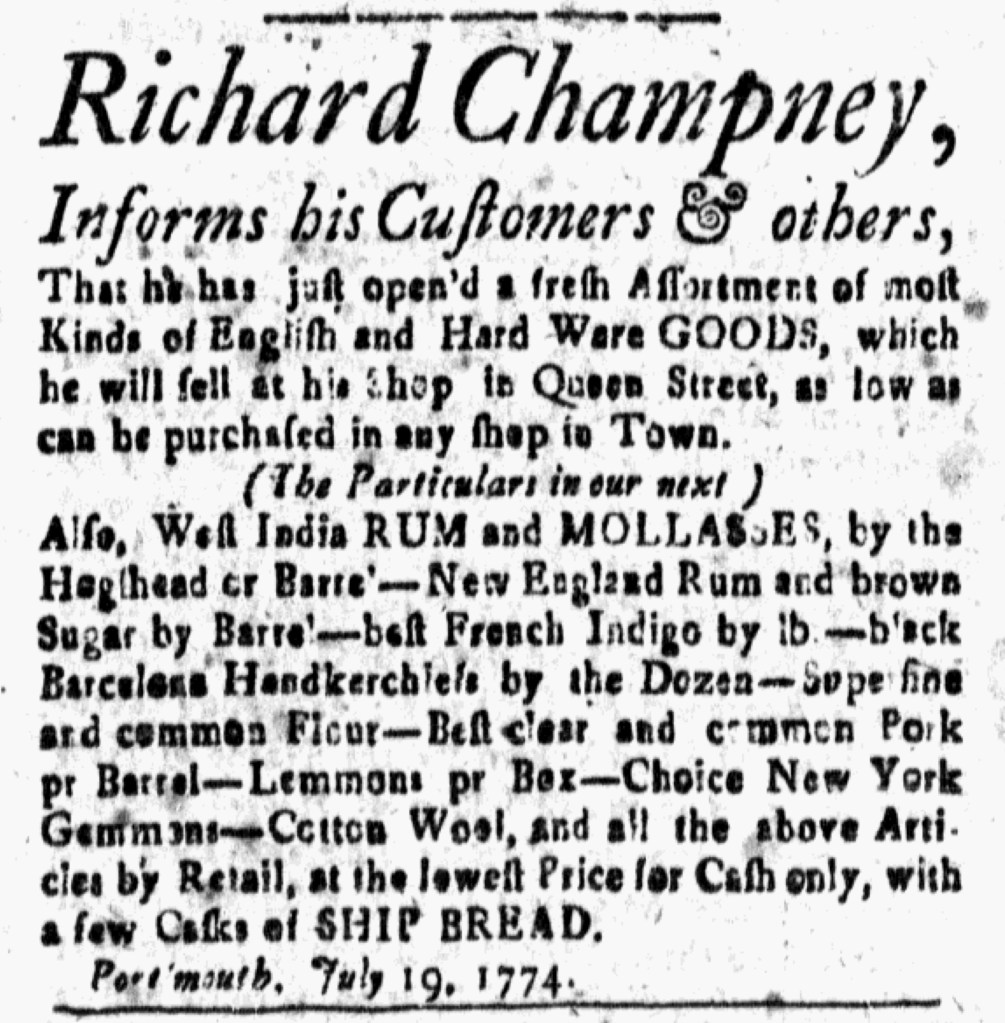

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“(The Particulars in our next)”

In the summer of 1774, Richard Champney took to the pages of the New-Hampshire Gazette to announce that he “has just open’d a fresh Assortment of most Kinds of English and Hard Ware GOODS” at his shop in Portsmouth. He pledged that customers could acquire his merchandise “as low as can be purchased in any shop in Town.” When his advertisement first ran on July 22, it did not list any of those items. Instead, a note promised, “The Particulars in our next.” Most likely the compositor devised that note due to lack of space in that issue; Champney’s advertisement appeared in the final column on the third page, the last of the content that would have been prepared for any edition.

The following week, however, his advertisement did not include the “Particulars.” It ran exactly as it had, without any revision, though the compositor managed to find room for a new advertisement that featured an extensive catalog of goods that John Penhallow “Imported from LONDON” and sold at his store. Had someone in the printing office overlooked the copy that should have appeared in Champney’s advertisement? Did the shopkeeper raise an objection when his complete advertisement did not run as planned? Was he frustrated that a competitor achieved greater visibility in the public prints even though he submitted his advertisement a week earlier?

Some exchange might have occurred between Champney and the printing office to rectify the situation. The complete advertisement finally found its way into print in the August 5 edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette, two weeks after the shopkeeper first alerted readers that he had a “fresh Assortment” of goods. It listed dozens of items to entice consumers, simultaneously demonstrating that the choices he offered to customers rivaled what Penhallow and other advertisers presented to the public. Promising the “Particulars” in the next issue may have encouraged anticipation among prospective customers, especially in an issue that included only one other advertisement for imported wares, that one from a milliner who promoted a narrow range of goods, but not following through on it did not serve Champney well when his competitors published their own catalogs of merchandise. Even though his complete notice eventually ran, any advantage from being the first in print had been squandered.