What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“… and many other Articles, as cheap as usual.”

Were advertisements in early American newspapers effective? Did they work? Did readers become consumers because advertisements incited demand? Did consumers select where they would shop because of the advertisements they encountered in the public prints. There are no easy answers to those questions.

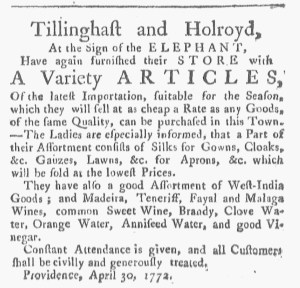

What can be asserted with more certainty is that many merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, and others who provided goods and services considered advertising worth the investment, so much so that they placed advertisements for years. Consider Nicholas Tillinghast and William Holroyd of Providence. As spring approached in 1774, they once again took to the pages of the Providence Gazette, this time promoting an assortment of “GARDEN SEEDS” as well as a “Variety of English and West India GOODS.” Perhaps seeing James Green’s advertisement for similar merchandise in the March 5 edition prompted them to insert their own notice in the next edition for fear of losing former and prospective customers to a competitor.

By that time, Tillinghast and Holroyd had been advertising in the Providence Gazette for years. The Adverts 250 Projecthas not featured every advertisement that they published, but it has examined several of them. On November 24, 1770, the partners announced that they “newly opened the Shop … at the Sign of the Elephant … where they have to sell a Variety of Articles.” A year later, they once again hawked “a Variety of well assorted GOODS,” noting that they stocked too many items “to be particularly mentioned in an Advertisement.” On May 16, 1772, they asserted that they sold a “Variety [of] ARTICLES … at as cheap a Rate as any Goods, of the same Quality, can be purchased in this Town.” They did not merely announce that they had merchandise for sale. Instead, Tillinghast and Holroyd repeatedly underscored that they offered choices to consumers and sometimes used prices to encourage prospective customers to choose their store over others. They did so once again in August 1773 when they directed “their old Customers and the Public” to a new shop “which they have built.” Their inventory consisted of “English Piece Goods, and Hard Ware of various Sorts, West-India Goods, Groceries and Wines of several Sorts.” The partners resorted to a familiar refrain: “the Particulars of which would be tedious to enumerate in an Advertisement.” Instead, they “can be better recounted to any who shall be pleased to make personal Application.” Tillinghast and Holroyd promised attentive customer service.

Did advertising work? Tillinghast and Holroyd thought that it worked well enough to justify placing yet another notice in the Providence Gazette in March 1774. If they suspected that advertising did not yield a return on their investment, would they have continued doing so?