What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Devil drives Lord North, and Lord North drives the People.”

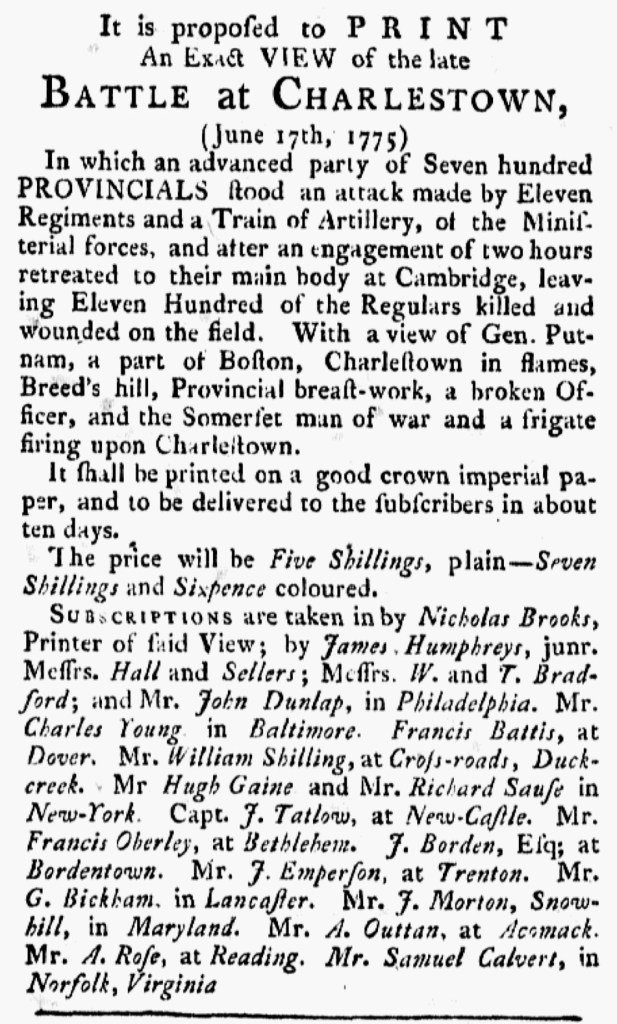

In the February 14, 1776, edition of the Constitutional Gazette, William Green, a bookbinder, advertised “three political Prints” for sale for one shilling each at his shop in Maiden Lane in New York. He listed the titles, but he did not describe them to prospective customers. Perhaps he did not wish to pay for the additional space in the newspaper. Perhaps he thought the titles provided sufficient description. Perhaps he considered the titles evocative enough to spark curiosity among readers, prompting them to visit his shop to discover for themselves what exactly each print depicted. After all, titles like “The Ministerial Robbers, or the Americans virtually represented in England” and “The Devil drives Lord North, and Lord North drives the People” simultaneously told a story and expressed support for the American cause. Notably, the purveyor of these “political Prints” was the first person to advertise Thomas Paine’s Common Sense outside of Philadelphia, doing so just eleven days after Robert Bell, the publisher of the first edition, announced its publication.

Readers may have been familiar with some of the political cartoons that Green advertised. In the fall of 1775, William Woodhouse, John Norman, and Robert Bell placed an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Journal to promote “The MINISTERIAL ROBBERS; or AMERICANS VIRTUALLY Represented in ENGLAND,” a “SATYRICAL PRINT” that “LATELY ARRIVED FROM LONDON.” Green may have sold copies from London or an American edition of the print.

Another of those political cartoons, “The Devil drives Lord North, and Lord North drives the People,” originated in London as “The State Hackney Coach,” a plate that adorned the London Magazine for December 1772. The print depicted a coach pulled by eight men rather than horses with Lord North, the prime minister, driving them. Most of those men did not have distinguishing features; they represented any of the members of Parliament and other officials who allowed the prime minister to dominate them. The first figure had a face that looked more like a rat than a man, additional commentary on the character of those members of Parliament. Henry Fox, one of North’s proteges, and Jeremiah Dyson, Lord of the Treasury, were recognizable. Although North drove the men with a whip, a devil perched on the back of the coach had his own whip that he used to steer North’s course. A caption above the image declared, “They go fast whom the Devil drives.” Inside the carriage, George III slept, apparently oblivious to any problems.

Green almost certainly displayed these political cartoons in his shop. Customers who came to purchase Common Sensewould have seen images that worked in tandem with Paine’s attitudes toward monarchy and calls to declare independence. They may even have decided to purchase both a print and a pamphlet, expressing their own political principles through the choices they made in the marketplace.