What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Fall GOODS, which were imported before the 1st of Dec.”

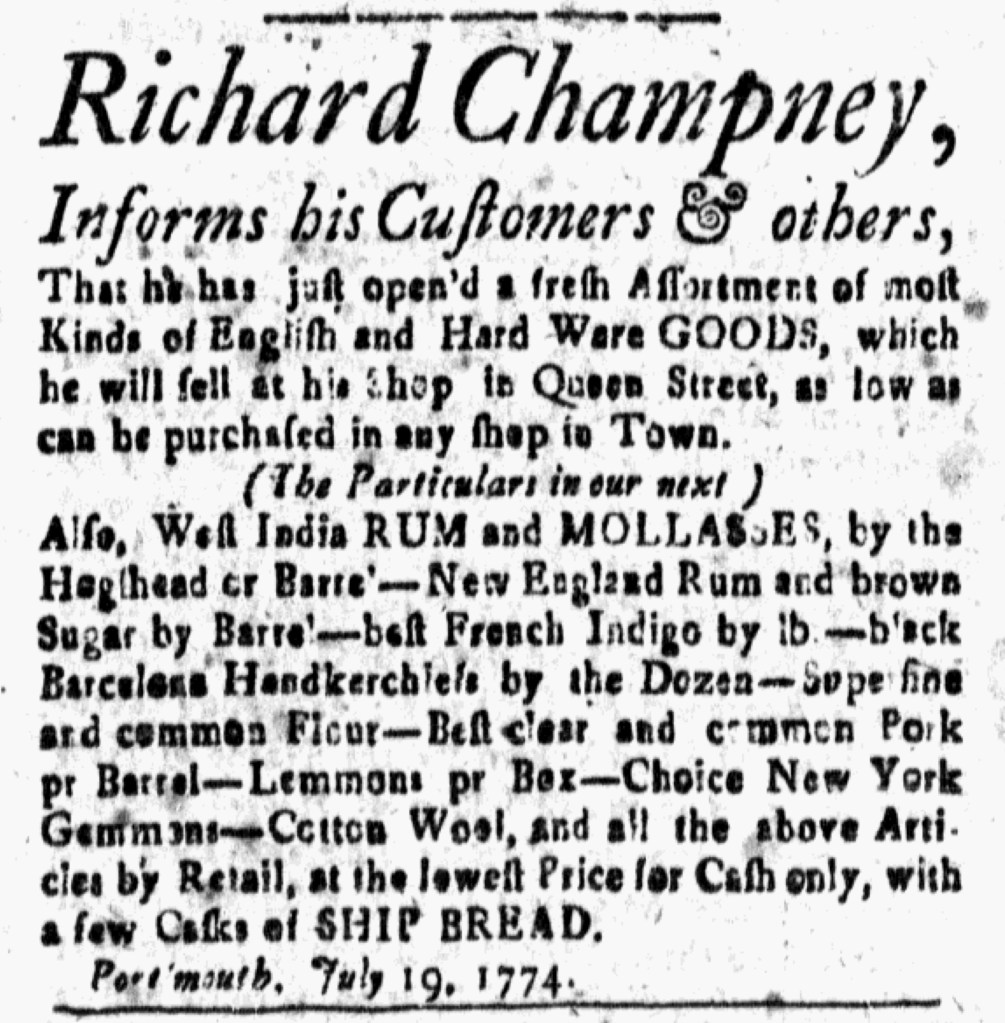

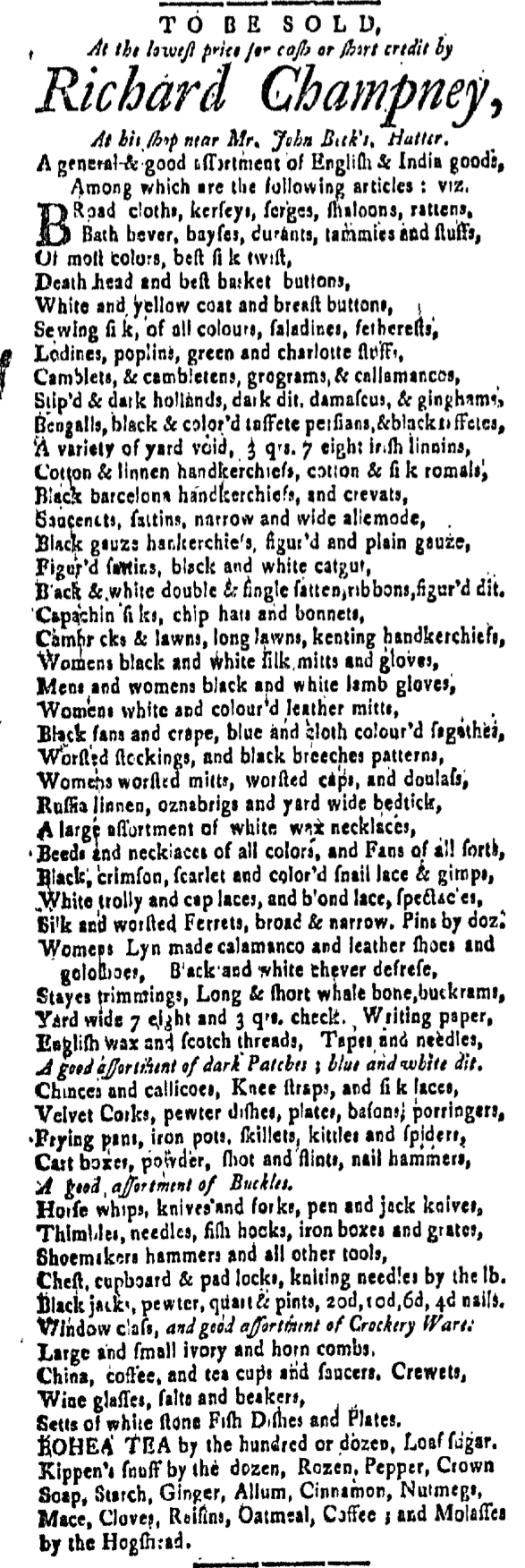

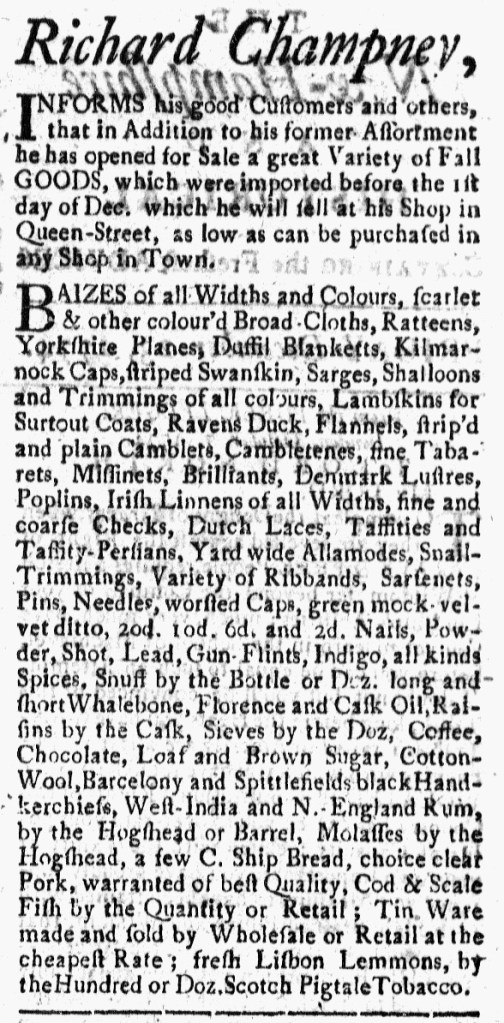

Richard Champney’s advertisement in the December 23, 1774, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette looked like many others that had appeared in that newspaper and others throughout the colonies for about two decades. The shopkeeper emphasized that he stocked “a great Variety of Fall GOODS” and promised competitive prices, declaring that consumers could acquire his merchandise “as low as can be purchased in any Shop in Town.” To demonstrate the array of choices he offered, he devoted most of his advertisement to an extensive list that included “BAIZES of all Widths and Colours,” “Shalloons and Trimmings of all colours,” “strip’d and plain Camblets,” “fine and coarse Checks,” a “Variety of Ribbands,” “worsted Caps,” and “Barcelony and Spittlefields black Handkerchiefs.” Although many of those textiles and accessories may not be immediately familiar to modern readers, they resonated with readers immersed in the consumer revolution of the eighteenth century. They fluently spoke the language of consumption.

Despite the similarities with longstanding forms of advertising, Champney’s notice included one detail that distinguished it from what he would have published even a month earlier. Although he had “opened” a new stock to supplement his “former Assortment,” those new goods “were imported before the 1st day of Dec[ember].” That clarification was important for the shopkeeper to bring to the attention of prospective customers in Portsmouth and nearby towns and anyone who might read the New-Hampshire Gazette far and wide. Champney explicitly specified that he observed the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement adopted by the First Continental Congress that went into effect on December 1. Since he had received this “great Variety of Fall GOODS” before that date, he could sell them with a clear conscience. Similarly, consumers could purchase them without worrying whether they aided the shopkeeper in breaking the agreement. For many years advertisers had noted when they imported their merchandise as a means of assuring prospective customers that they carried new items of the latest styles and taste. After December 1, 1774, however, when a shipment arrived had political significance and new sorts of ramifications for both advertisers and buyers.