What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He hereby recommends to them, as a person qualified to serve them on the best terms.”

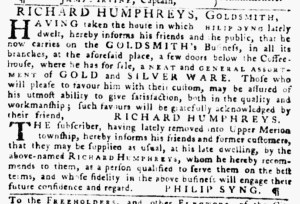

As fall arrived in 1772, Richard Humphreys took to the pages of the Pennsylvania Gazette to inform prospective customers that he “now carries on the GOLDSMITH’s Business, in all its branches” at “the house in which PHILIP SYNG lately dwelt” near the London Coffee House in Philadelphia. In an advertisement in the September 23 edition, he made appeals similar to those advanced by other artisans who placed notices in the public prints. He emphasized the choices that he offered to consumers, asserting that he stocked a “NEAT and GENERAL ASSORTMENT of GOLD and SILVER WARE.” Humphreys also highlighted his own skills, promising that customers “may be assured of his utmost ability to give satisfaction, both in the quality and workmanship” of the items he made, sold, and mended.

In addition to those standard appeals, Humphreys published an endorsement from another goldsmith, Philip Syng! Syng reported that he recently relocated to Upper Merion. In the wake of his departure from Philadelphia, he “informs his friends and former customers, that they may be supplied as usual, at his late dwelling, by the above-named RICHARD HUMPHREYS.” Syng did not merely pass along the business to Humphreys. He also stated that he recommended him “as a person qualified to serve” his former customers “on the best terms, and whose fidelity” in the goldsmith’s business “will engage their future confidence and regard.” With this endorsement, Humphreys did more than set up shop in Syng’s former location. He became Syng’s successor. In that role, he hoped to acquire the clientele that Syng previously cultivated. Syng’s endorsement also enhanced his reputation among prospective customers.

Artisans frequently stressed their skill and experience in their advertisements. Some detailed their training or their previous employment to assure prospective customers of their abilities and competence. Such appeals required readers to trust the claims made by the advertisers. Endorsements also required trust, but they did not rely solely on the word of the advertisers themselves. In this instance, another goldsmith, one known to “friends and former customers” in Philadelphia, verified the claims that Humphreys made in his advertisement. Syng staked his own reputation by endorsing Humphreys, a marketing strategy intended to give prospective customers greater confidence in the goldsmith who now ran the shop near the London Coffee House.