What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 year ago today?

“ON July last, twenty-first day, / My servant, JOHN SMITH, ran away.”

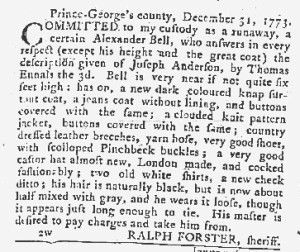

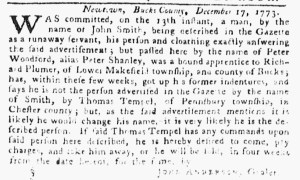

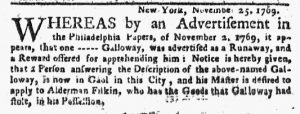

Advertisements about indentured servants who ran away before completing their contracts appeared regularly in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet in the 1770s. In “Reading the Runaways,” David Waldstreicher demonstrates that similar advertisements ran in newspapers throughout the Middle Atlantic colonies during the era of the American Revolution.[1] As I have examined newspapers from New England to Georgia for the Adverts 250 Project, I have encountered advertisements describing runaway servants and offering rewards for detaining and returning them in newspapers in every region. They were so common that many issues featured multiple advertisements, some of them concerning two or more indentured servants that made a getaway together.

Given the ubiquity of those advertisements, John Whitehill wanted to increase the chances that readers noticed, read, and remembered his advertisement. Rather than write formulaic copy, he composed a poem of more than a dozen rhyming couplets. “ON July last, twenty-first day,” the first two lines read, “My servant, JOHN SMITH, ran away.” The poem was easy to spot on the page of the October 9, 1775, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. The compositor indented each line, creating white space that distinguished the advertisement from other content. The irregular lengths of each line of the poem meant even more white space on the right. On a page of news and advertisements printed in orderly columns, justified on the left and on the right, the significant amount of white space in Whitehill’s advertisement made it easy to spot.

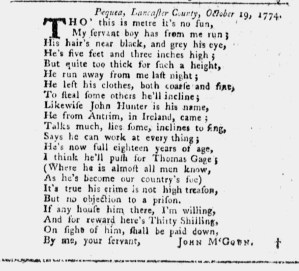

Once readers looked more closely, the opening couplet may have inspired even more curiosity. “Age twenty-five years, and no more,” Whitehill’s poem continued, “I think his heighth is five feet four; / Black curled hair, and slender made, / And is a weaver by his trade.” Additional couplets described Smith’s clothing, the items he took with him to set up trade somewhere else, and his arrival from Newry on the Renown the previous fall. One couplet warned others not to aid Smith: “Should any persons him conceal, / No doubt with them I think to deal.” The final couplets offered a reward and named the aggrieved master: “SIX LAWFUL DOLLARS I will pay; / I live in Salsbury, Pequea, / And further to oblige you still, / My name is junior JOHN WHITEHILL.” The reward and the names of the servant and the advertiser were the only part of the poem in all capitals, likely intended to draw attention to the incentive for reading the advertisement and assisting Whitehill.

The poem certainly was not Milton nor Shakespeare, but the format of Whitehill’s runaway advertisement made it different (and more entertaining) than any of the other five notices placed for the same purposes in that issue of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. The attention it garnered may very well have been worth the time and effort that Whitehill invested in writing the poem. For other examples of masters adopting this strategy, see James Gibbons’s advertisement about Catherine Waterson in the December 21, 1769, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette and John McGoun’s advertisement about John Hunter in the October 26, 1774, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette.

**********

[1] David Waldstreicher, “Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 56, no. 2 (April 1999): 243-272.