What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

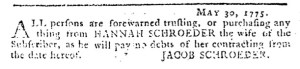

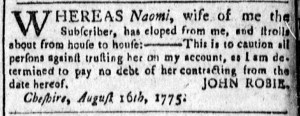

“This is to caution all persons against trusting her on my account.”

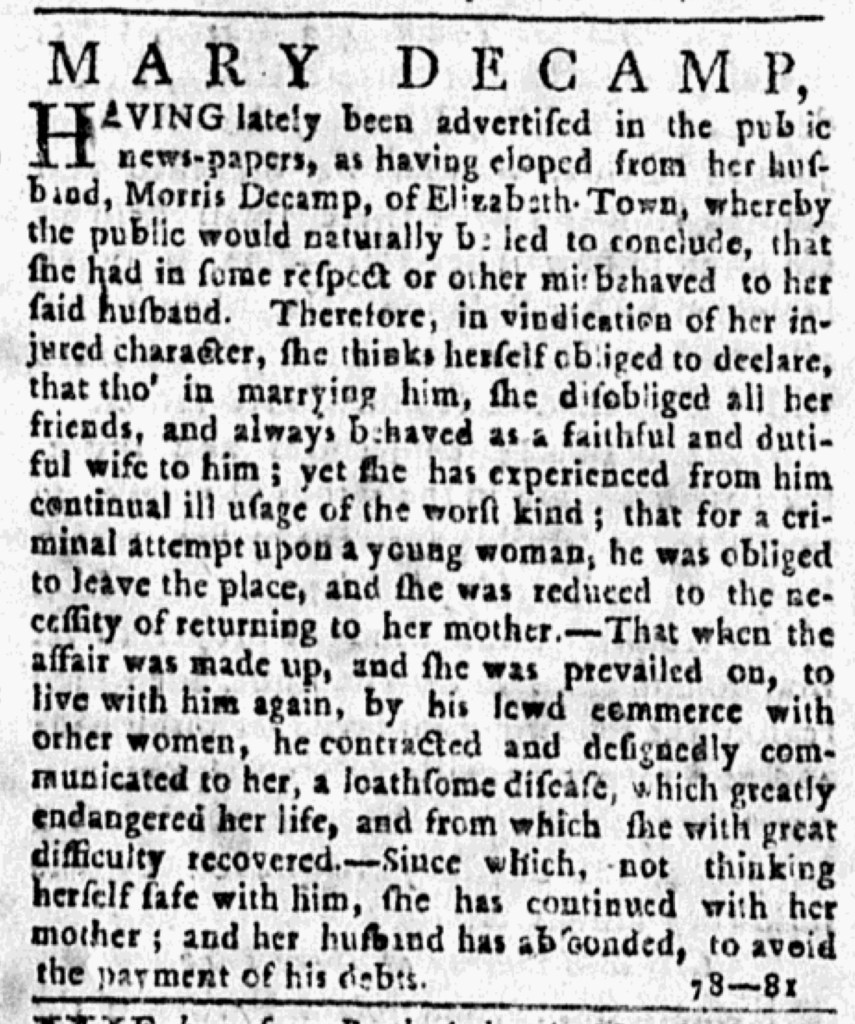

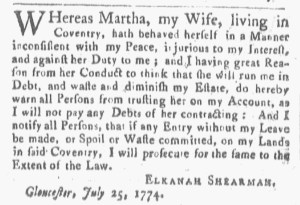

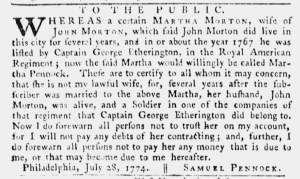

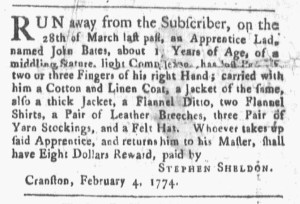

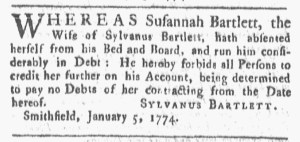

It was a familiar sight. Advertisements about runaway wives peppered the pages of early American newspapers. Husbands, like John Robie, took to the public prints to warn that since their wives, in this case Naomi Robie, “eloped” from them that those women no longer had access to credit. “This is to caution all persons against trusting [Naomi] on my account,” John proclaimed, “as I am determined to pay no debt of her contracting from the date hereof.” He presented himself as the aggrieved husband, yet his wife likely had her own version of the origins of their marital discord. Running away may have been the best option to remove her from a bad situation.

When John placed his advertisement about Naomi in the August 25, 1775, edition of the Essex Journal, it ran immediately after a petition from “The FEMALE SUPPORTERS of LIBERTY” reprinted from the Newport Mercury. “WHEREAS our country has long groaned under the oppression of a tyrannical ministry; and has lately been invaded by our enemies, who stained the land with the blood of our dear brethren,” the petition began, “THEREFORE we, the subscribers, are determined to defend our liberties, both civil and religious, to do the utmost that lies in our power.” These women took a stand to defend their “liberties” in a manner considered acceptable, while Naomi had asserted her liberty in an inappropriate manner. “We do not mean to take up arms,” the petitioners continued, “for that does not become our sex.” They affirmed that they knew their proper place, unlike Naomi who departed from John’s household “and strolls from house to house.” The petitions vowed to “put our hands to the plough, hoe and rake, and till the ground, for our men to go to the assistance of our distressed brethren, there to conquer our enemies or die in the attempt.” Those women faced uncertain futures, realizing that the deaths of husbands, fathers, and brothers would be sacrifices that affected them and their families. They also pledged to “forsake the gaieties of the world,” such as abiding by nonimportation and nonconsumption agreements, “before we will give up our country’s liberties and religion.”

The petition ended with a vow of mutual support: “Our company is to consist of as many true daughters of liberty as will undertake the noble cause.” Furthermore, “No one to be admitted who retains any of the tory principles.” Women (and men) recognized legitimate ways for women to participate in politics and advocate for their own interests, but only to any extent. In this instance, advocacy extended to words and deeds that supported women (and their country) collectively, defending their “liberties and religion,” but not to condoning individual acts of resistance like Naomi Robie’s plan for self-determination when they ran counter to her husband’s wishes. Many of the women who signed the petition may have privately sympathized with Naomi, but the press carried nothing but condemnations of her actions even as it celebrated the “FEMALE SUPPORTERS of LIBERTY” and their commitment to the American cause.