What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

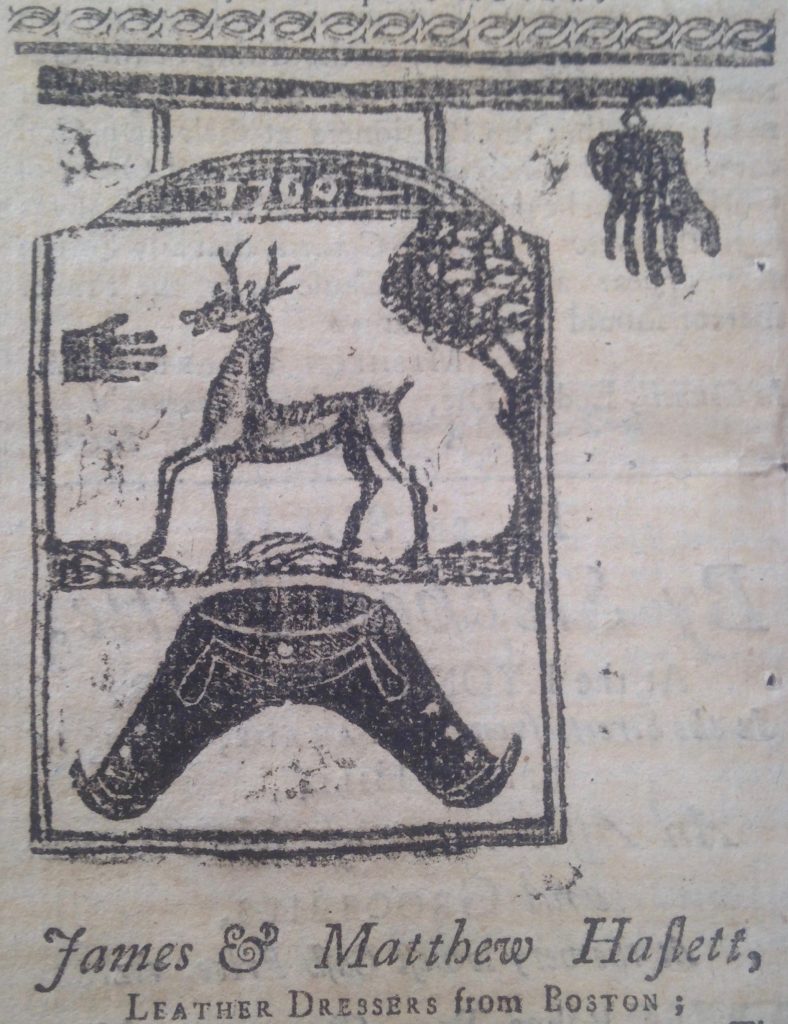

“Leather and Breeches may also be had at said Nash’s Store, the Sign of the Buck and Glove.”

When Joseph Nash advertised a “large Parcel of Deers Leather” and “Buckskin Breeches” in the Providence Gazette in the fall of 1768, he informed readers that they could purchase these items at two locations in Providence. Prospective customers could deal directly with Nash “At the North End of the Town of Providence.” Alternately, they could also visit “Nash’s Store, the Sign of the Buck and Glove, just below the Mill-Bridge, in Providence.” Nash reported that Levi Hall and N. Metcalf, “Leather-Dressers,” had set up shop at that location. It appears that Hall and Metcalf may have been tenants rather than employees of Nash, but their relationship extended to assisting each other with their business endeavors. Nash’s advertisement concluded with a note that Hall and Metcalf wished to procure sheepskins, “for which they will give Cash or Leather.”

Whatever their relationship, Nash was the focal point of the advertisement, in terms of both the typography and the appeals made to prospective customers. “Joseph Nash” served as the headline for the advertisement, appearing on a line of its own and in much larger font than the rest of the copy in the advertisement. In that regard “Joseph Nash” matched the treatment given to the names of other advertisers in their notices, including “Joseph Olney,” “John White,” and “Charles Stevens.” The compositor also applied this design to advertisements placed by partners, giving each partner his own line: “JOSEPH / AND / Wm. RUSSELL” and “THURBER / AND / CAHOON.” With the exception of the masthead, the only other text of similar size in that issue came from the headline of an advertisement in which the printers promoted the “New-England / TOWN and COUNTRY / Almanack.” Both “New-England” and “Almanack” appeared in the same significantly larger font as “Joseph Nash.” Even though “LEVI HALL, and N. METCALF” appeared in capitals in the middle of the advertisement, “Joseph Nash” was the name readers would notice at a glance. It dominated the advertisement and the rest of the page on which it appeared.

Nash’s appeals to customers also overshadowed any independent work undertaken by Hall and Metcalf. Before he even mentioned that they occupied his store at the Sign of the Buck and Glove, Nash addressed the quality and range of choices among his “large Parcel of Deers Leather,” stating that the pieces were “dressed in the neatest Manner, and well so sorted, from the thickest Buckskin to the finest Doe; so that any Gentleman may have his Choice.” Furthermore, his “ready made Buckskin Breeches” were also “done in the neatest Manner, by a Workman from London.” Unlike Hall and Metcalf, Nash certainly supervised the work done by an employee at his location at the north end of Providence. The remainder of the advertisement mentioned that prospective customers could purchase the same items from Hall and Metcalf, but did not promote the quality, prices, or choices of their inventory, which also included “Sheep and Lambskins … and Sheeps Wool.”

Nash’s advertisement certainly promoted his own products. It also granted increased visibility to Hall and Metcalf even though the focus remained primarily on their collaboration with Nash. That likely served Nash’s purposes, especially if he wished to retain as much of his share of the local market as possible while also making Hall and Metcalf’s business a viable enough enterprise that they could continue as tenants or otherwise operating his second location at the Sign of the Buck and Glove.