What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Pieces taken out of News papers, and not written by the Author of COMMON SENSE.”

The final page of the Pennsylvania Evening Post was once again ground zero for the dispute between Robert Bell, the publisher of the first edition of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and subsequent unauthorized editions, and William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, the printers of the Pennsylvania Journal entrusted by Paine to publish a “NEW EDITION … With ADDITIONS and IMPROVEMENTS in the BODY of the WORK.” Paine previously participated in the dispute, but he seemingly withdrew in favor of letting the printers duke it out in the public prints.

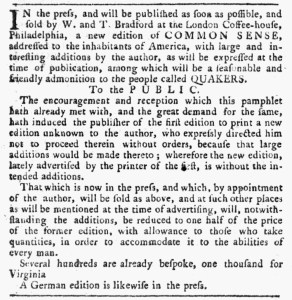

The Bradfords’ expanded edition had been in the press for a few weeks, but on February 14, 1776, they announced in their own newspaper that “THIS DAY WILL BE PUBLISHED AND SOLD … THE NEW EDITION OF COMMON SENSE.” The following day, they ran a new advertisement in the Pennsylvania Evening Post and then updated it on February 20. To make that edition more appealing than any of the editions published by Bell, the Bradfords proclaimed, “The Additions which are here given, amount to upwards of one Third of any former Edition.” They also acknowledged that Bell had been advertising “ADDITION to COMMON SENSE,” but they alerted readers that Bell was trying to pull a fast one. The “ADDITIONS” that Bell marketed “consist of Pieces taken out of News Papers, and not written by the Author of COMMON SENSE.” Paine had worked exclusively with the Bradfords on the “ADDITIONS and IMPROVEMENTS.” The Bradfords also listed several booksellers who stocked their new edition. Benjamin Towne, the printer of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, was not among them, but he certainly generated revenue from publishing the advertisements that the Bradfords and Bell submitted to his printing office.

Right next to the Bradfords’ advertisement, as had been the case on other occasions, appeared Bell’s advertisement for “Large ADDITIONS to COMMON SENSE.” Those “ADDITIONS” included “the following interesting subjects,” “American Independency defended by Candidus,” and “The Propriety of Independancy, by Demophilus,” and “Observations on Lord North’s Conciliatory Plan, by Sincerus.” This version of the advertisement added “The American Patriot’s Prayer,” left out of Bell’s previous notice, to entice prospective customers. Bell also pirated “AN APPENDIX TO COMMON SENSE, together with an ADDRESS to the people called QUAKERS, on their Testimony concerning Kings and Government.” Like the Bradfords, he charged “one shilling ONLY” and made “allowance to those who buy quantities.” In other words, the printers of Common Sense and related materials offered discounts to retailers who purchased in volume to sell the pamphlet in their own shops and others who bought multiple copies to distribute to friends, relatives, and associates. The contents of Paine’s political pamphlet made it popular, yet the advertisements in the Pennsylvania Evening Post and other newspapers also helped raise awareness of Common Sense.