What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The REPRESENTATIONS of Governor Hutchinson, and others, Contained in certain LETTERS transmitted to England.”

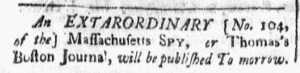

Among the various advertisements in the October 19, 1773, edition of the Essex Gazette, Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall, the printers of the newspaper, offered a pamphlet “Just published in Boston” and available at their printing office. Many readers likely already knew about the contents of the pamphlet, “The REPRESENTATIONS of Governor Hutchinson, and others, Contained in certain LETTERS transmitted to England, and afterwards returned from thence, and laid before the GENERAL ASSEMBLY of the MASSACHUSETTS-BAY, Together with the RESOLVES of the two Houses thereon.” Acquiring the pamphlet and reading the correspondence for themselves, however, gave colonizers an opportunity to see for themselves exactly what Thomas Hutchinson and others had reported to ministers and members of Parliament in letters that had not been intended for public consumption. Purchasing and perusing the pamphlet also presented another means of participating in politics.

As Jordan E. Taylor explains in Misinformation Nation: Foreign News and the Politics of Truth ion Revolutionary America, this was not the first instance of printers publishing private letters from colonial officials to associates in London.[1] In the wake of the arrival of British soldiers in Boston in 1768, Benjamin Edes and John Gill, printers of the Boston-Gazette, published Letters to the Ministry from Governor Bernard, General Gage, and Commodore Hood. The Halls reprinted the pamphlet and sold it in Salem. Taylor describes the letters as “quite benign – dull even,” yet a “few passages, nevertheless, aroused indignation,” including “Bernard’s suggestion that the Massachusetts charter be altered to weaken the council and strengthen the office of the governor.” In addition, letters from customs commissioners recommended “two or three Regiments” to “restore and support Government” in Boston. From the perspective of the printers and many colonizers, these letters were “hard evidence that a group of officials was conspiring to intentionally exaggerate the disorder in Massachusetts and bring troops into Boston.”

In 1773, the Representations of Governor Hutchison and Others further misrepresented the situation in Massachusetts, at least according to colonizers who advocated for the patriot cause and who recognized a pattern in how the misunderstandings between the colonies and Parliament occurred. This pamphlet included letters from Thomas Hutchinson, Andrew Oliver, the lieutenant governor, and Charles Paxton, a customs officer. One passage written by Hutchinson addressed “the abridgment of the colonists’ liberties,” though the governor “claimed that he was predicting, rather than prescribing, that those liberties might eventually be limited.” Paxton requested “two or three regiments” or else “Boston will be in open rebellion.” Taylor notes that printers “widely shared the letters in their newspapers,” making them widely accessible and perhaps even generating demand for a volume that collected them together. The letters gained sufficient interest for the pamphlet to go through ten editions as colonizers examined what Hutchinson and others had written for themselves and constructed their own narrative that the Representations and representations of colonial officials amounted to misrepresentations that caused and exacerbated the imperial crisis.

**********

[1] For a more complete account of Letters to the Ministry and Representations of Governor Hutchinson, see Jordan E. Taylor, Misinformation Nation: Foreign News and the Politics of Truth in Revolutionary America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022), 52-54.