What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

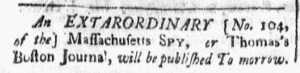

“An EXTRAORDINARY … will be published To morrow.”

“Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” That was Isaiah Thomas’s message to readers of the Massachusetts Spy. The printer included an announcement in the January 28, 1773, edition, alerting subscribers and other readers that “An EXTRAORDINARY [No. 104, of the] Massachusetts SPY, or Thomas’s Boston Journal, will be published To morrow.” Unlike the supplements and postscripts that sometimes accompanied early American newspapers, Thomas considered the extraordinary, distributed on a Friday, a separate issue. As he noted in his announcement, it had its own number, 104, following “NUMB. 103,” distributed on Thursdays as usual for the Massachusetts Spy. Thomas or a compositor who worked in his printing office updated the masthead to include “EXTRAORDINARY.”

The “extra” issue consisted of two pages, compared to four for the weekly standard issues of the Massachusetts Spy and other American newspapers published at the time. It consisted almost entirely of a single item from the “HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES” in Boston, along with half a column of news from Salem and one short advertisement for grocery items. (In similar circumstances, other printers took the opportunity to insert advertisements about the goods and services available at their printing offices.) The main item that prompted publication of the extraordinary was an “ANSWER to [Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s] SPEECH, to both Houses, at the opening of this session.” Representatives “ORDERED” that a committee comprised of “Mr. Adams, Mr. Hancock, Mr. Bacon, Col. Bowes, Major Hawley, Capt. Darby, Mr. Philips, Col. Thayer, and Col. Stockbridge” compose that answer. Members of the committee agreed with the governor that “the government at present is in a very disturbed state.” They did not, however, identify the same causes. “[W]e cannot ascribe it to the people’s having adopted unconstitutional principles,” as the governor claimed. Instead, they believed that problems arose as a result of “the British House of Commons assuming and exercising a power inconsistent with the freedom of the constitution to give and grant the property of the colonists, and appropriate the same without their consent.”

When Thomas published the extraordinary, he already had a reputation as a printer devoted to principles espoused by the patriots. The masthead for his newspaper described it as “A Weekly, Political, and Commercial PAPER:– Open to ALL Parties, but Influenced by None,” yet immediately below that sentiment appeared this message: “DO THOU Great LIBERTY INSPIRE our Souls,– And make our Lives in THY Possession happy,– Or our Deaths glorious in THY JUST Defence.” Thomas likely had two reasons for quickly publishing the committee’s response as an extraordinary. He scooped his competitors while also disseminating rhetoric that matched his own views. (Most other newspapers printed in Boston included the response as part of their coverage when they distributed their next weekly edition, but that took several days or, in the case of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter, printed by Loyalist Richard Draper, an entire week.) Thomas previously published the governor’s speech as an extraordinary, dated and distributed on the same day as the weekly issue on Thursday, January 7. In so doing, he upheld his pledge that the Massachusetts Spy was “Open to ALL Parties,” yet publishing the governor’s speech also kept colonizers informed about the dangers they faced from the narrative of recent events that Hutchinson constructed. Releasing the committee’s response as its own extraordinary on a day that no other newspapers were published in Boston and announcing his plans to issue that extraordinary may have garnered more attention more quickly to the version of events that matched Thomas’s own views. Patriots and imperial officials vied over how to represent what was occurring in Boston and throughout the colonies. Thomas may have considered getting the committee’s response to the governor in print as quickly as possible an important counteroffensive against the governor’s speech that he published three weeks earlier.