What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“BOXES of MEDICINES fitted up as usual.”

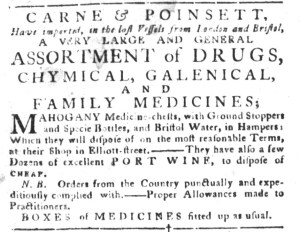

As fall approached in 1772, Carne and Poinsett alerted readers of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal that they imported and sold a “VERY LARGE AND GENERAL ASSORTMENT of DRUGS, CHYMICAL, GALENICAL, AND FAMILY MEDICINES.” They competed with Thomas Stinson, who acquired his “FRESH SUPPLY of DRUGS, CHYMICAL and GALENICAL, With most Family Medicines now in Use” directly from “their ORIGINAL Warehouses,” and Edward Gunter, who stocked a “large and complete ASSORTMENT OF DRUGS and MEDICINES” imported via “the last Vessels from LONDON.”

In addition to carrying similar merchandise, each of these entrepreneurs offered an ancillary service for the convenience of their customers. Carne and Poinsett promoted “BOXES of MEDICINES fitted up as usual.” Their competitors gave more elaborate descriptions of this service. Gunter declared that he supplied “BOXES of MEDICINES, with Directions, for Plantations and Ships Use, prepared in the best Manner.” Similarly, Stinson explained that “BOXES of MEDICINES, with Directions for PLANTATIONS and SHIPS Use, are faithfully prepared” at his shop.

Providing these boxes kept Gunter, Stinson, and Carne and Poinsett competitive with each other, eliminating the possibility that prospective customers would turn to one who offered the convenience of such boxes medicines over one who did not. Yet marketing this service to customers did not constitute the sole reason for assembling these eighteenth-century versions of first aid kits. Doing so augmented sales beyond medicines that customers actually needed to medicines that they might need at some time in the future. Entrepreneurs who ran apothecary shops used the combination of uncertainty and distance to their advantage, realizing that many prospective customers did not have easy access to medicines and needed to plan for various possibilities rather than acquire remedies only when need became apparent. It mattered little to these entrepreneurs whether their customers ever used the medicines in the boxes they “fitted up as usual.” They traded in the security offered by the convenience of having various medicines on hand even if the buyers never needed to administer some of them.