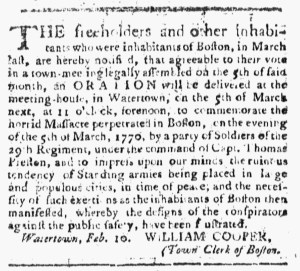

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“An ORATION will be delivered … to commemorate the horrid Massacre perpetrated in Boston.”

It was an annual tradition that commenced the year after the Boston Massacre. The residents of the town gathered for an oration that commemorated the event. James Lovell spoke in 1771, Joseph Warren in 1772, Benjamin Church in 1773, and John Hancock in 1774. Joseph Warren once again delivered the oration in 1775, about six weeks before the imperial crisis became an armed conflict at the battles at Lexington and Concord and just three months before Warren, a major general in the colony’s militia, was killed during the Battle of Bunker Hill. As the siege of Boston continued in 1776, the tradition continued, though in Watertown where the Massachusetts Provincial Congress met rather than in occupied Boston

About three weeks in advance, Thomas’ Massachusetts Spy, which had relocated to Worcester from Boston just as hostilities commenced, carried a notice for the “freeholders and other inhabitants who were inhabitants of Boston, in March last.” It advised that “agreeable to their vote in a town-meeting legally assembled on the 5th of said month,” the fifth anniversary of the Boston Massacre, “an ORATION will be delivered at the meeting-house, in Watertown, on the 5th of March next … to commemorate the horrid Massacre perpetrated in Boston … by a party of Soldiers of the 29th Regiment, under the command of Capt. Thomas Preston.” As usual, the oration would not merely honor those who died when British soldiers fired into a crowd of protestors; the speaker would also “impress upon our minds the ruinous tendency of Standing armies being placed in large and populous cities, in time of peace.” The presence of British soldiers in Boston led to what colonizers often called the “bloody Tragedy.” The oration was also a call to action, asserting “the necessity of such exertions as the inhabitants of Boston then manifested, whereby the designs of the conspirators against the public safety, have been frustrated.” The annual gathering had even greater significance now that colonizers were fighting a war against British troops and many of them increasingly contemplated declaring independence rather than seeking redress of their grievances within the imperial system. With an advertisement in the public prints, the organizers hoped to draw crowds for the oration and, in turn, strengthen the resolve of those who attended.