What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

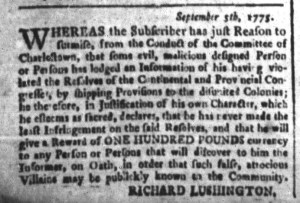

“He … declares, that he has never made the least Infringement on the said Resolves.”

Richard Lushington was serious about defending his reputation. When the merchant suspected that rumors circulated about alleged misconduct, he placed an advertisement in the South-Carolina and American General Gazette to offer a substantial reward to anyone who revealed the source. In a notice dated September 5, 1775, Lushington declared that he “has just Reason to surmise, from the Conduct of the Committee of Charlestown” that was responsible for enforcing nonimportation and nonexportation agreements “that some evil, malicious Person or Persons has lodged an Information of his having violated the Resolves of the Continental and Provincial Congresses, by shipping Provisions to the disunited Colonies.” The Continental Association did not prohibit exporting commodities to Britain, Ireland, and colonies in the West Indies until September 10, but perhaps the reports contended that Lushington had been overzealous in how much and how quickly he exported provisions to colonies in the Caribbean that had not signaled support for the American cause. Had the merchant attempted to sidestep the Continental Association, abiding by the letter but not the spirit?

Lushington denied that he acted inappropriately. “[I]n justification of his own Character, which he esteems as sacred,” he proclaimed that “he has never made the least Infringement on the said Resolves.” The merchant was so anxious to address the allegations that offered “a Reward of ONE HUNDRED POUNDS currency to any Person or Persons that will discover to him the Informer, on Oath, in order that such false, atrocious Villains may be publickly known in the Community.” He may have been especially keen to address the charges manufactured against him because, as Amy Pastan explains, he was a Quaker and thus an outsider among the predominantly Anglican population in Charleston. “While Quakers were tolerated in the southern port city,” Pastan notes, “their anti-slavery views set them apart from the Charleston elite.” Whatever challenges he faced as fall arrived in 1775, Lushington later demonstrated his allegiance to the American cause by serving as captain of a Patriot militia company known as the Free Citizens of Charleston as well as the Jews Company because several Jewish men, also outsiders in Charleston, served in it.

For more on Lushington and the Free Citizens of Charleston, visit “Rediscovering Charleston’s Revolutionary Outsiders.”