What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He now carries on the Peruke-Making Business in all its Branches.”

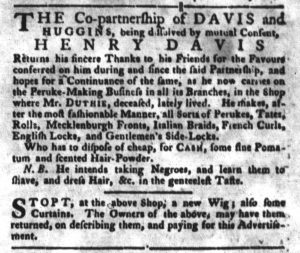

Henry Davis, a wigmaker, hairdresser and barber, did not have only a single purpose for placing an advertisement in the April 10, 1770, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. Instead, he pursued several in the course of just a few lines, all of them ultimately promoting his business in one way or another.

He opened by extending “his sincere Thanks” to former customers now that the “Co-partnership of DAVIS and HUGGINS” had been “dissolved by mutual Consent.” He expressed appreciation for “the Favours conferred on him” and requested “a Continuance of the same” in his new endeavor. Now that Davis opened his own shop, he hoped to maintain the client base that he had established while in partnership with Huggins.

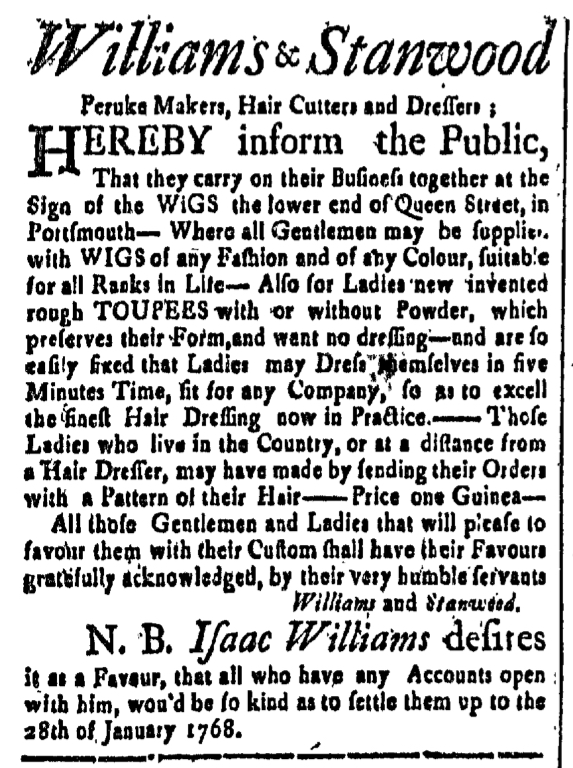

He also hoped to expand his clientele. To that end, he addressed former and prospective customers alike when he listed and described the various kinds of wigs he made “after the most fashionable Manner.” He carried “all Sorts of Perukes, Tates, Rolls, Mecklenburgh Fronts, Italian Braids, French Curls, English Locks, and Gentlemen’s Side-Locks.” Davis knew that discerning readers could differentiate among the assorted styles. In addition to the wigs, Davis sold accessories, including “fine Pomatum and scented Hair-Powder.”

As he launched his new business, the wigmaker also intended to expand his staff in order to provide additional services to his clients. He previewed his plan to acquire enslaved workers and teach them “to shave, and dress Hair, &c. in the genteelest Taste.” The skill of those assistants would testify to Davis’s own expertise. Their presence in his shop would contribute to the pampering of clients. He envisioned that his future success depended in part on the involuntary labor of others.

Finally, Davis advised readers that he had “STOPT” a new wig as well as some curtains. In other words, someone presented him with items to purchase but he instead confiscated them because he believed they were stolen. He invited the rightful owner to retrieve them upon offering an accurate description and “paying for this Advertisement.” This demonstrated his character as he commenced a new enterprise. It also revealed that some colonists attempted to participate in the consumer revolution and keep up with the latest fashions through unsavory means.

In quick succession, Davis announced the end of his partnership with Huggins, attempted to cement relationships with former clients, provided an overview of the products and services available at his new shop, noted that he intended to acquire additional staff, and invited the victim of a theft to retrieve goods he recovered. Each of these aspects of his advertisement served to bolster confidence in his abilities as a wigmaker and entrepreneur among prospective customers.