What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

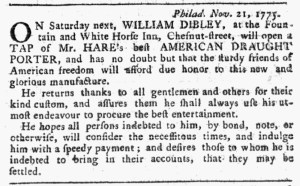

“WILLIAM DIBLEY … will open a TAP of Mr. HARE’s best AMERICAN DRAUGHT PORTER.”

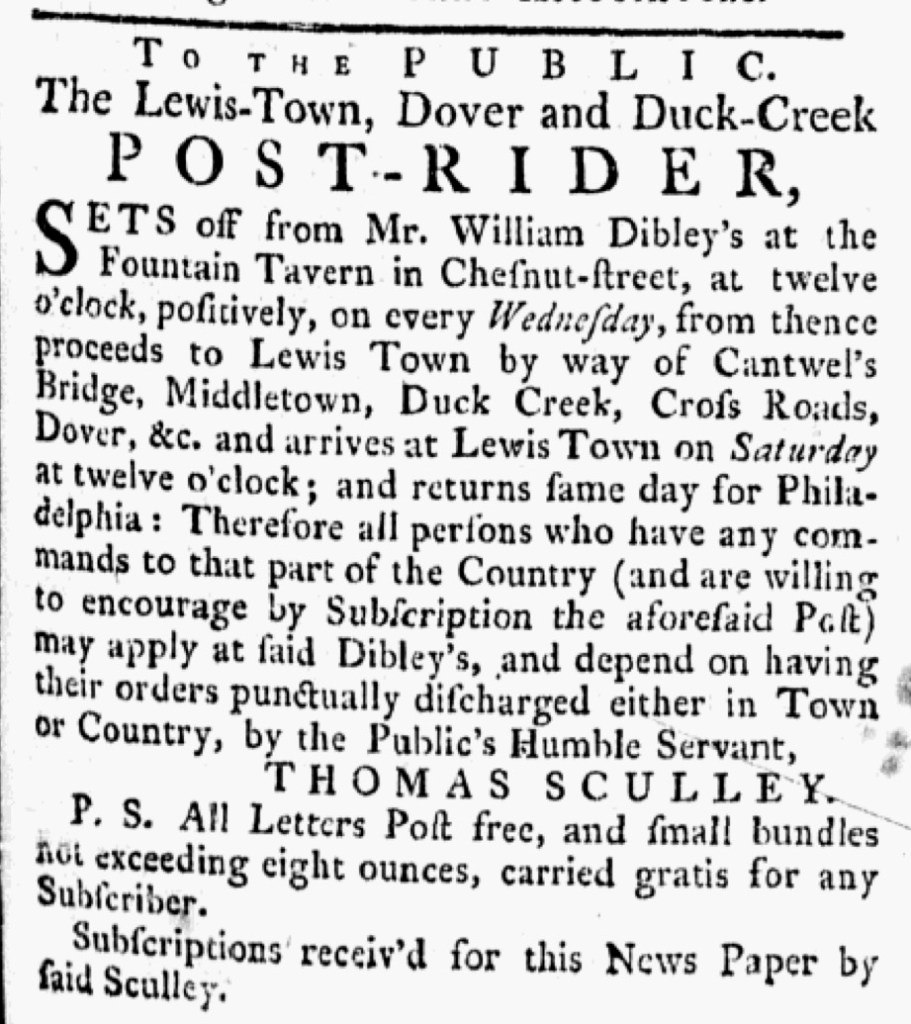

William Dibley was no stranger to advertising his tavern in the public prints. In February 1775, he announced that he “removed from the Cross Keys … to the Fountain and Three Tuns.” Both were located on “Chesnut-street” in Philadelphia, so his regular patrons did not have to go far to continue enjoying Dibley’s hospitality, yet he made sure that both “his Friends in particular and the public in general” knew about the “considerably improved” amenities available at his new location.

Nine months later, Dibley ran an advertisement in which he “returns thanks to all gentlemen and others for their kind custom, and assures them he shall always use his utmost endeavour to procure the best entertainment.” By that time, he updated the name of his establishment to the Fountain and White Horse Inn, perhaps an effort to retain some continuity with a device, the Fountain, that had marked the location while simultaneously distinguishing his business from the one that Anthony Fortune previously operated at the same location, exchanging the Three Tuns for the White Horse. Dibley’s expression of gratitude suggested that patrons continued gathering at his tavern when he rebranded it.

He aimed to give them more reasons to gather at the Fountain beyond the amenities he highlighted in his earlier advertisement, proclaiming that on Saturday, November 25, he would “open a TAP of Mr. HARE’s best AMERICAN DRAUGHT PORTER.” This porter was for patriots! Dibley declared that he “has no doubt but that the sturdy friends of American freedom will afford due honor to this new and glorious manufacture.” As George Washington and the American army continued the siege of Boston and the Second Continental Congress continued meeting in Philadelphia, Dibley offered an opportunity for supporters of the American cause to drink a porter brewed in the colonies as they gathered to socialize and discuss politics at his tavern. The tavernkeeper made the porter, a new product, the highlight of a visit to the Fountain, announcing when he would “open a TAP” to create anticipation among prospective patrons. They may have expected an informal ceremony and a round of toasts to mark the occasion, another enticing reason to visit the Fountain on that day. Consumption certainly had political overtones at the time. Dibley tapped into the discourses about purchasing American goods when he marketed a visit to his tavern,