What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

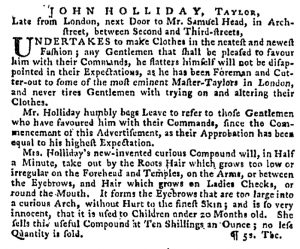

“Mrs. Holliday’s new-invented curious Compound.”

Women actively participated in the colonial marketplace as retailers of imported goods and sellers of other wares, especially in the major port cities. Historians have estimated, for instance, that as many as four out of ten shopkeepers in Philadelphia were women. Yet an overview of advertising from the period does not testify to the extensive presence of women as sellers, producers, and suppliers (as opposed to merely taking on the role of consumers) in the eighteenth century. Although some female entrepreneurs did advertise in newspapers, they were disproportionately underrepresented in that medium. Women were even less likely to distribute other forms of advertising – trade cards, billheads, broadsides, notices on magazine wrappers – in the eighteenth century, despite some notable exceptions.

Some female entrepreneurs resorted to roundabout means of promoting their business endeavors in the public prints. John Holliday’s wife, identified only as “Mrs. Holliday,” appended an announcement about her “new-invented curious Compound” to her husband’s advertisement for his tailoring shop. Throughout the eighteenth century, some women took that means of injecting their own marketing messages into a public discourse of commerce dominated by men. In addition to husbands and wives, sometimes fathers and daughters or brothers and sisters or widows and close family friends or business associates issued joint advertisements that first detailed the goods and services offered by a man and then turned to another enterprise conducted by a woman. Only on exceptionally rare occasions did shared newspapers advertisements first promote a woman’s business endeavors before turning to her male counterpart.

Certainly some of the decision to place joint advertisements resulted from minimizing expenses devoted to marketing. The pattern of privileging husbands and other male relations or associates over women, however, suggests that some female entrepreneurs felt a bit of apprehension about too boldly making their business activities visible to the general public, even as they needed to attract customers from among that public. Appending their own advertisements to those placed by men who presumably oversaw their dealings to some extent or another had the effect of providing implicit masculine endorsement as well as suggesting that female entrepreneurs operated under appropriate male supervision.