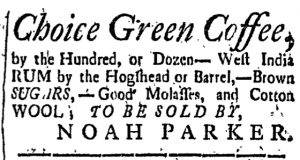

My second round of Adverts 250 was an interesting one to say the least. It took my experience from last semester and tried to find better sources. Sometimes I failed and at other times I excelled. Last semester I used JSTOR for all my sources but I found that to be difficult. This semester I tried to broaden my sources. I found a lot of better fitting sources and I found some very interesting stories to tell. This made my analysis that much better because I found sources I really enjoyed reading. Overall, this part of the project was the easiest. Of course there is always room for improvement. If I ever had an opportunity to do this project again, I think I would want to do more research on words I do not know in the advertisements. Plus, for some reason I thought brewers and distillers were one and the same. I learned something new.

I will say there were some crazy moments, however. I was juggling multiple projects, one of which was giving me loads of stress, but that’s a whole other story. In the beginning, I thought I was going to have an upper hand on the project because I had already done it once before, but nonetheless, life is full of curveballs and it was not as easy as I thought it would be. I wouldn’t have it any other way though, because it would not have been so satisfying to finish if it had been as easy as I expected.

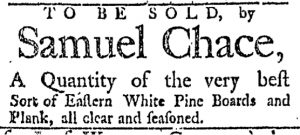

I got to learn so many new things about life in the colonial and Revolutionary eras. I think my favorite thing to learn about was Eastern White Pine and the Pine Tree Riot of 1772 because that’s not something in most of the history books but it had an impact on the rising tension between the English and the colonists that led to the Revolutionary War. Another interesting thing I learned about was William Jackson. He had an interesting start thanks to his mother and he is riddled into American history, such as not participating in the non-importation agreements to being captured when he tried to flee Boston because he was a Loyalist.

I think the most rewarding part of this experience was the fact that I knew people were reading my work and getting something out of it. Most of the things I wrote about I had never even heard of before so I hope to some people who read my analysis learned something too. We gained this opportunity to read into advertisements and got the chance to delve into why certain items were so popular while others were unique. Being able “do history” is such a rewarding experience because there is always something new to learn about and then can teach that new information to someone else.

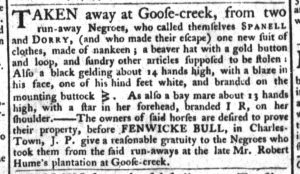

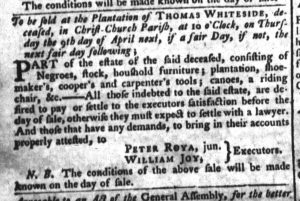

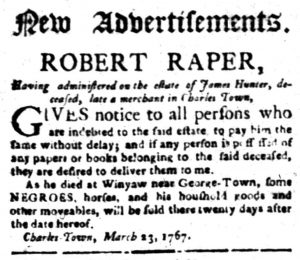

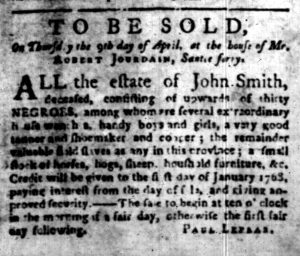

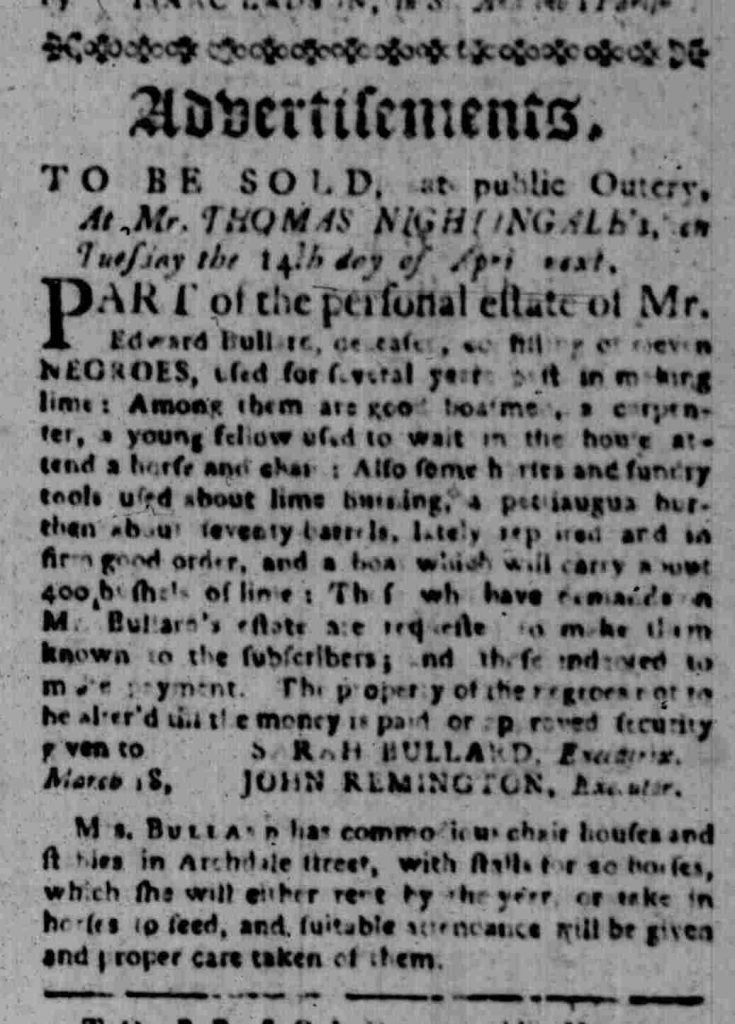

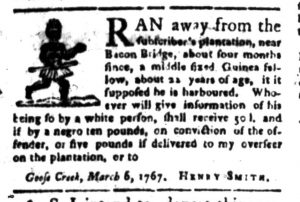

Overall, I once again thoroughly enjoyed working on this project. Learning about the past helps us in the future and I find it fascinating how some of the items being advertised can lead to much larger stories that could even relate to today. I am looking forward to continuing the Slavery Adverts 250 in a week and delving into the commercial trade of slaves.