What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He wants good Hoops, Boards and Staves, some very good Horses, and a new Milch Cow. (51)”

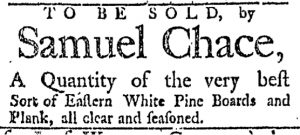

Readers of the Providence Gazette may have noticed that some, but not all, of the advertisements concluded with a number in parentheses. In the February 18, 1769, edition, Samuel Chace’s advertisement for a “NEW and general Assortment of English and India GOODS,” for instance, ended with “(51)” on the final line. Thomas Greene’s advertisement for a “fresh Assortment of DRY-GOODS” immediately above it featured “(64).” Elsewhere in the issue, other advertisements included “(55)” and “(62).” The first three advertisements all had “(67)” on the final line. What purpose did these numbers serve?

They were not part of the copy submitted by advertisers. Instead, the compositor inserted these numbers to record the first issue in which an advertisement appeared. According to the masthead, the February 18 edition was “NUMB. 267.” The “(67)” indicated three of the advertisements made their inaugural appearance in that issue. Similarly, “(51)” was associated with issue number 251 and “(64)” first ran in issue number 264. The printer and compositor made use of these numbers for bookkeeping and other aspects of producing the Providence Gazette. They made it much easier to determine when it was time to remove an advertisement from subsequent issues.

That the advertisements in the February 18 edition did not appear in numerical or chronological order also demonstrates another aspect of newspaper production. Compositors set the type for each advertisement only once. Once the type had been set, however, compositors moved advertisements around to fit them on the page. In general, no advertisements received privileged placement based on how many weeks they ran in the newspaper, nor did the compositor attempt to organize them according to any principles other than the most efficient use of space. Advertisements making their inaugural appearance, however, were an exception to that rule. In the February 18 issue, all of the advertisements marked “(67)” appeared before any other advertisements. Printers and compositors did give new advertisements a place of prominence, knowing that readers sometimes looked for those in particular. Although the Providence Gazette did not do so, some newspapers even ran special headings for “New Advertisements” to distinguish them from others that already ran in previous issues.

Printers and compositors intended for subscribers and other readers to ignore the numbers they inserted on the final line of many advertisements. Those numbers made important information readily accessible to those who worked in printing offices, but it was not information intended to shape public reaction to the contents of the paid notices.