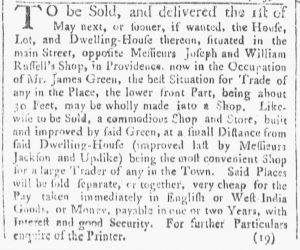

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A faithful Account of the Proceedings of the Subscribers and Non-Subscribers.”

The commodification of the American Revolution began several years before the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord. As the imperial crisis unfolded, printers marketed a variety of books, pamphlets, and engravings that commemorated current events while simultaneously informing consumers of the rift between the colonies and Britain.

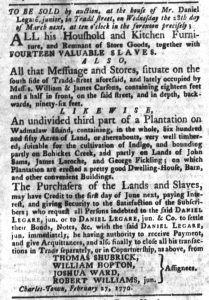

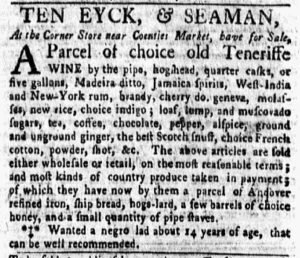

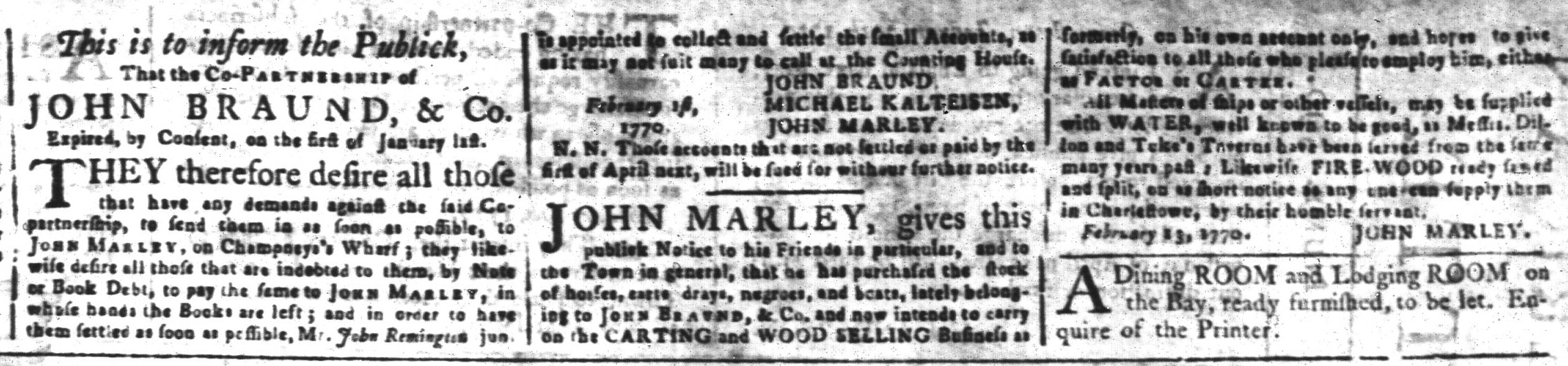

Consider, for instance, an advertisement that appeared in the March 20, 1770, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. It announced a “Compilation” of documents related to the colony’s nonimportation agreement was “In the PRESS, and speedily will be published.” That compilation contained “ALL the LETTERS which have been written FOR and AGAINST the RESOLUTIONS” along with “Copies of the different Resolutions proposed to be signed.” It also included various lists, including “the Names of the Gentlemen who compose the Committee” that enforced the agreement and “a List of the Non-Subscribers” so readers would know which members of the community worked against the interests of the colony. To that end, the collection featured “Remarks on the Conduct and Writings” of the “Non-Subscribers.” The compiler of these documents wished to educate readers about the debates over the boycott, inserting “a Translation of the Latin Verses, Phrases, &c. made Use of in the said Letters.” Not everyone possessed a classical education, but all colonists could participate in the debates and make decisions about their own conduct. Nonimportation was not restricted to highbrow households. In addition to all that, the compilation included “several other interesting Particulars relative to the above Resolutions.” Through a series of documents and commentaries, it provided a history of recent events, a “faithful Account of the Proceedings of the Subscribers and Non-Subscribers.”

Purchasing this compilation gave colonists another means of participating in protests against the duties on imported goods imposed by Parliament in the Townshend Acts. Doing so enhanced feelings of connection to others who supported nonimportation agreements in South Carolina and, more generally, throughout the colonies. Colonists envisioned a time when importation would resume after Parliament relented and repealed the unpopular duties. When that happened, the compilation would become a memento that reminded those who purchased it of the events they had witnessed, the history they had played a part in shaping. Owning a copy gave colonists yet another way to express their support for the American cause.