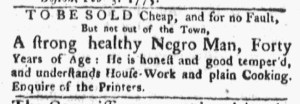

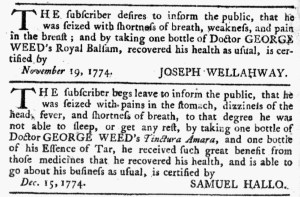

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“By taking one bottle of Doctor GEORGE WEED’s Royal Balsam, recovered his health.”

A notice signed by Joseph Wellahway appeared in the February 28, 1774, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger for the purpose of “inform[ing] the public, that he was seized with shortness of breath, weakness, and pain in the breast; and by taking one bottle of Doctor GEORGE WEED’s Royal Balsam, recovered his health as usual.” Wellahway “certified” that testimonial on November 19, 1774. Immediately below, Samuel Hallo offered a more elaborate endorsement, signed on December 15, 1774. He recounted that he “was seized with pains in the stomach, dizziness of the head, fever, and shortness of breath, to that degree he was not able to sleep, or get any rest.” He finally found relief “by taking one bottle of Doctor GEORGE WEED’s Tinctura Amara, and one bottle of his Essence of Tar.” When he did that, “he received such great benefit from those medicines that,” like Wellahway, “he recovered his health, and is able to go about his business as usual.”

Weed, who regularly placed advertisements in Philadelphia’s newspapers, did not supplement these testimonials with a notice of his own, not even to direct prospective patients to his shop. He likely believed that he had established such a reputation in the city that he did not need to do so. It was not the first time he adopted that strategy. An advertisement in the Pennsylvania Chronicle five years earlier featured testimonials from Jacob Burroughs, Margaret Lee, Tabitha Wayne, and Elizabeth Beach. Each of those names may have seemed more plausible to skeptical readers than Joseph Wellahway and Samuel Hallo. In December 1772, Weed concluded an advertisement with a note from a minister to certify that he “was under the Instructions and Directions of a judicious Practitioner of Physic, in New-England, from some Years,” though that missive was dated almost two decades earlier. Some or all these endorsements may have been genuine, yet Weed might have manufactured some of them to market his remedies. Prospective patients, then as now, likely embraced the veneer of authenticity in hopes that the medicines would indeed deliver the promised results.