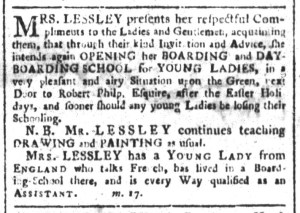

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“She intends again OPENING her BOARDING and DAY-BOARDING SCHOOL.”

Mrs. Lessley ran a “BOARDING and DAY-BOARDING SCHOOL for YOUNG LADIES” in Charleston in the 1770s. She closed the school for a while, as schoolmasters and schoolmistresses often did for various reasons, but, as spring arrived in 1775, she took to the pages of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette to announce that she planned on “again OPENING” her school “after the Easter Holiday.” She decided to do so, she stated, at the “kind Invitation and Advice” of “Ladies and Gentlemen” familiar with her school, offering an implicit endorsement she hoped would convince prospective pupils and their families.

Lessley also gave information about others who worked at her school. “MR. LESSLEY continues teaching DRAWING and PAINTING as usual,” enriching the curriculum offered by his wife. Readers, especially former students, may have assumed that was the case, but they did not necessarily know about a new employee. The schoolmistress reported that she “has a YOUNG LADY from ENGLAND who talks French, has lived in a Boarding-School there, and is every Way qualified as an ASSISTANT.” Those cosmopolitan skills and experiences enhanced the education that Lessley provided for her charges. Her assistant aided in teaching a language considered a marker of gentility among the gentry and those who aspired to join their ranks. Perhaps she even served as the primary instructor for that subject. She may have consulted with Lessley on replicating an English boarding school without students having to cross the Atlantic while also serving as a role model for how “YOUNG LADIES” should comport themselves at such a school.

The schoolmistress gave less attention to the amenities at her school, though she did mention that it was located “in a very pleasant and airy Situation upon the Green.” With classes slated to begin sometime after April 16, she assured prospective students and their families that they would live and learn in a comfortable environment. She also indicated that she would commence lessons “sooner should any young Ladies be losing their Schooling.” In other words, if other schoolmasters and schoolmistresses closed or suspended their schools, Lessley would gladly accept their students. She hoped that these additional appeals in combination with her description of those who taught at her school would help in encouraging prospective pupils and their families to enroll.