GUEST CURATOR: Massimo Sgambati

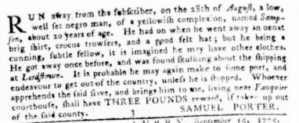

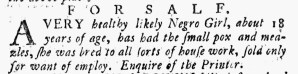

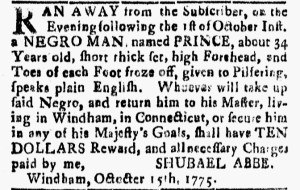

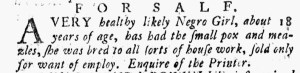

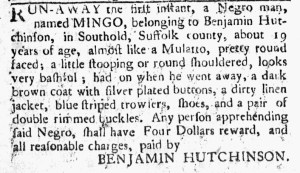

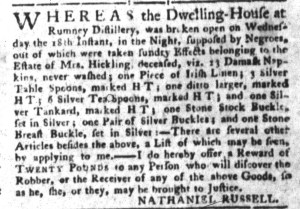

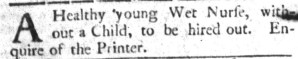

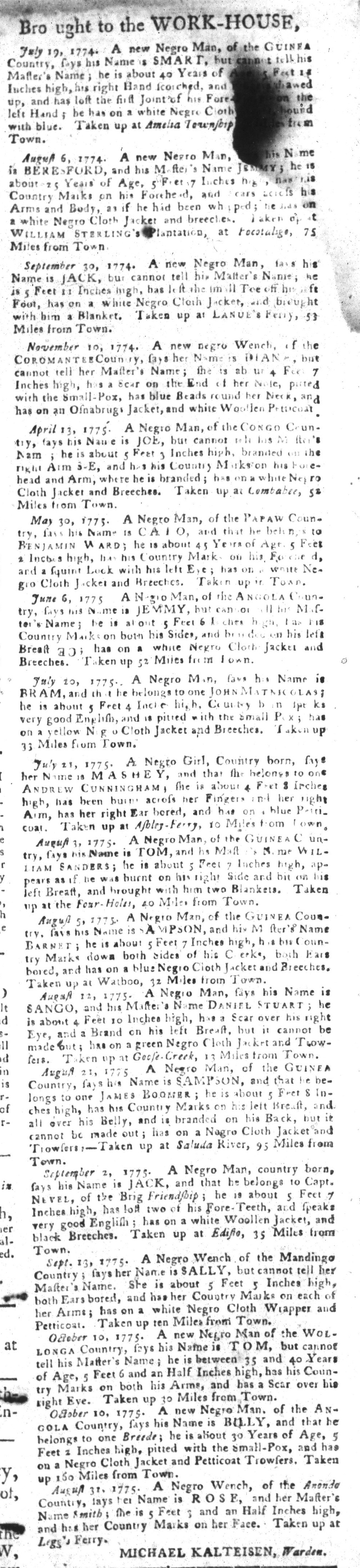

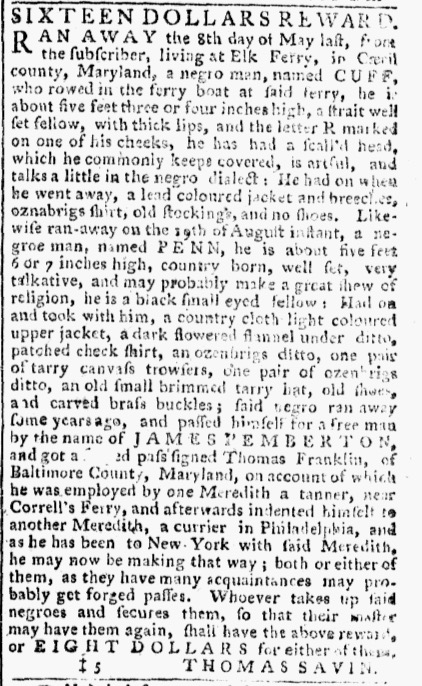

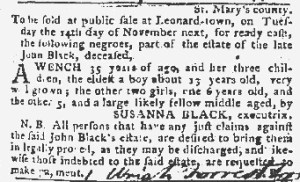

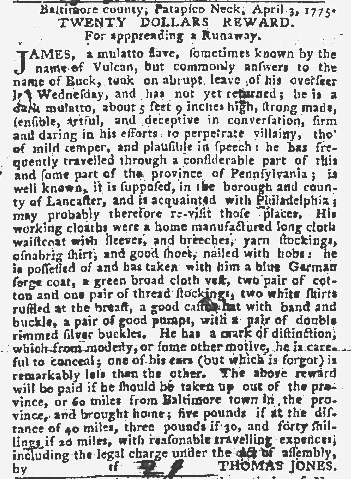

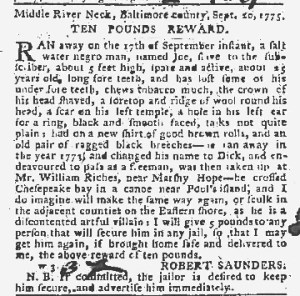

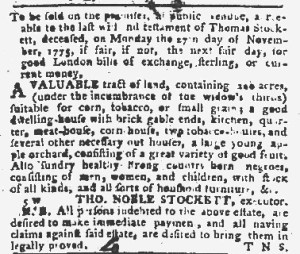

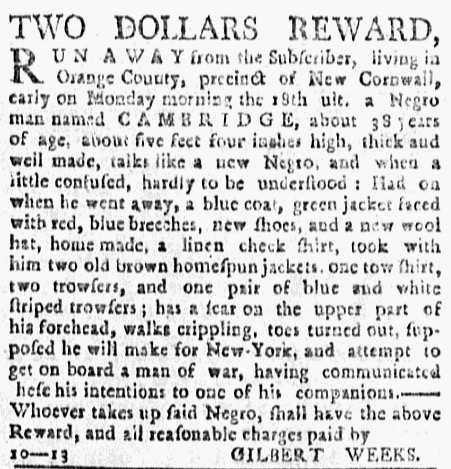

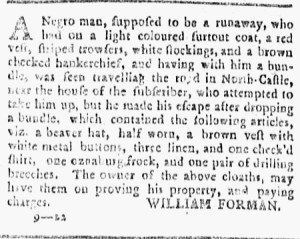

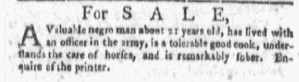

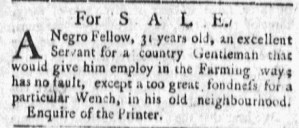

The Slavery Adverts 250 Project chronicles the role of newspaper advertising in perpetuating slavery in the era of the American Revolution. The project seeks to reveal the ubiquity of slavery in eighteenth-century life from New England to Georgia by republishing advertisements about enslaved people – for sale as individuals or in groups, wanted to purchase or for hire for short periods, runaways who liberated themselves, and those who were subsequently captured and confined in jails and workhouses – in daily digests on this site as well as in real time via the @SlaveAdverts250 Twitter feed, utilizing twenty-first-century media to stand in for the print media of the eighteenth century.

The project aims to provide modern audiences with a sense of just how often colonizers encountered these advertisements in their daily lives. Enslaved men, women, and children appeared in print somewhere in the colonies almost every single day. Those advertisements served as a constant backdrop for social, cultural, economic, and political life in colonial and revolutionary America. Colonizers who did not purport to own enslaved people were still confronted with slavery as well as invited to maintain the system by purchasing enslaved men, women, and children or assisting in the capture of so-called “runaways” who sought to free themselves from bondage. The frequency of these newspaper advertisements suggests just how embedded slavery was in colonial and revolutionary American culture in everyday interactions beyond the printed page.

These advertisements also testify to the experiences of enslaved men, women, and children, though readers must consider that those experiences have been remediated through descriptions offered by enslavers rather than enslaved people themselves. Often unnamed in the advertisements, enslaved men, women, and children were not invisible or unimportant in early America.

From compiling an archive of digitized eighteenth-century newspapers to identifying advertisements about enslaved men, women, and children in those newspapers to preparing images of each advertisement to posting this daily digest, Massimo Sgambati served as guest curator for this entry. He completed this work as part of the Summer Scholars Program, funded by a fellowship from the D’Amour College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Assumption University in Worcester, Massachusetts, in Summer 2025.

These advertisements appeared in colonial American newspapers 250 years ago today.

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********

**********