What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

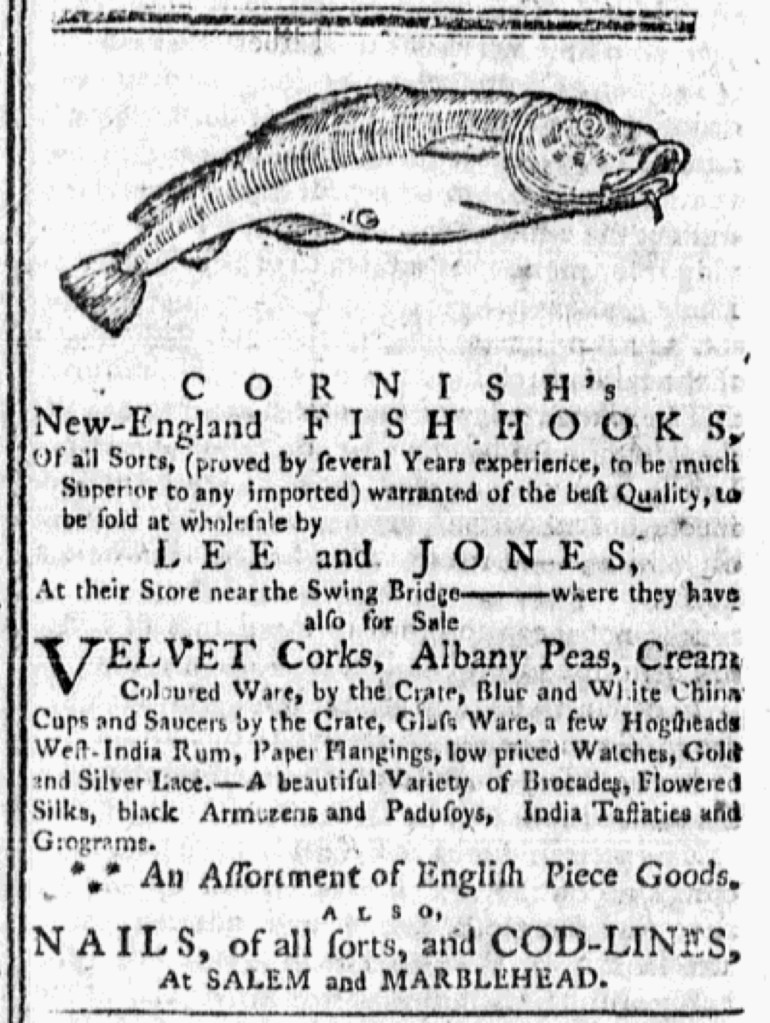

“CORNISH’s New-England FISH HOOKS.”

Lee and Jones stocked a variety of merchandise at “their Store near the Swing Bridge” in Boston in February 1775, but they made “CORNISH’s New-England FISH HOOKS” the centerpiece of their advertisement in the February 9 edition of the Massachusetts Spy. Not only did they list that product first and devote the most space to describing it, but they also adorned their advertisement with a woodcut depicting a fish. That image previously appeared in advertisements that Abraham Cornish placed in the Massachusetts Spy in March 1772 and March 1773. Either Lee and Jones acquired the woodcut from Cornish when they composed the copy for their notice or Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy, held the woodcut for Cornish and determined that advertisers promoting his product could use it in their notices. It was not the first time that Lee and Jones distributed “CORNISH’s New-England Cod-Fish HOOKS.”

By the time that Lee and Jones ran their advertisement, Cornish had established a familiar brand. In addition to advertising in the Massachusetts Spy, he also advertised in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter and Salem’s Essex Gazette. His marketing efforts regularly touted the approval he received when “Fishermen … made trial of his Hooks” and found them “much superior to those imported from England.” Lee and Jones deployed similar appeals when they proclaimed that the hooks had been “Proved by several Years experience, to be much Superior to any imported.” Such assertions held even greater significance with the Continental Association, a nonimportation pact, in effect and the imperial crisis becoming even more dire. In protest of the Coercive Acts passed in response to the Boston Tea Party, colonizers vowed not to import good from Britain. The Continental Association called for encouraging domestic manufactures or goods produced in the colonies as alternatives to imported items. Cornish has been making that case for his product for several years, as many readers likely remembered when they saw Lee and Jones’s advertisement for “CORNISH’s New-England FISH HOOKS.”