What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Impress’d with a sense of the prejudice and injury I have done my country, humbly ask their forgiveness.”

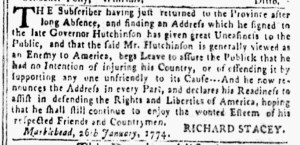

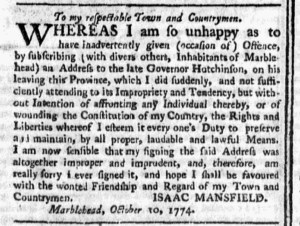

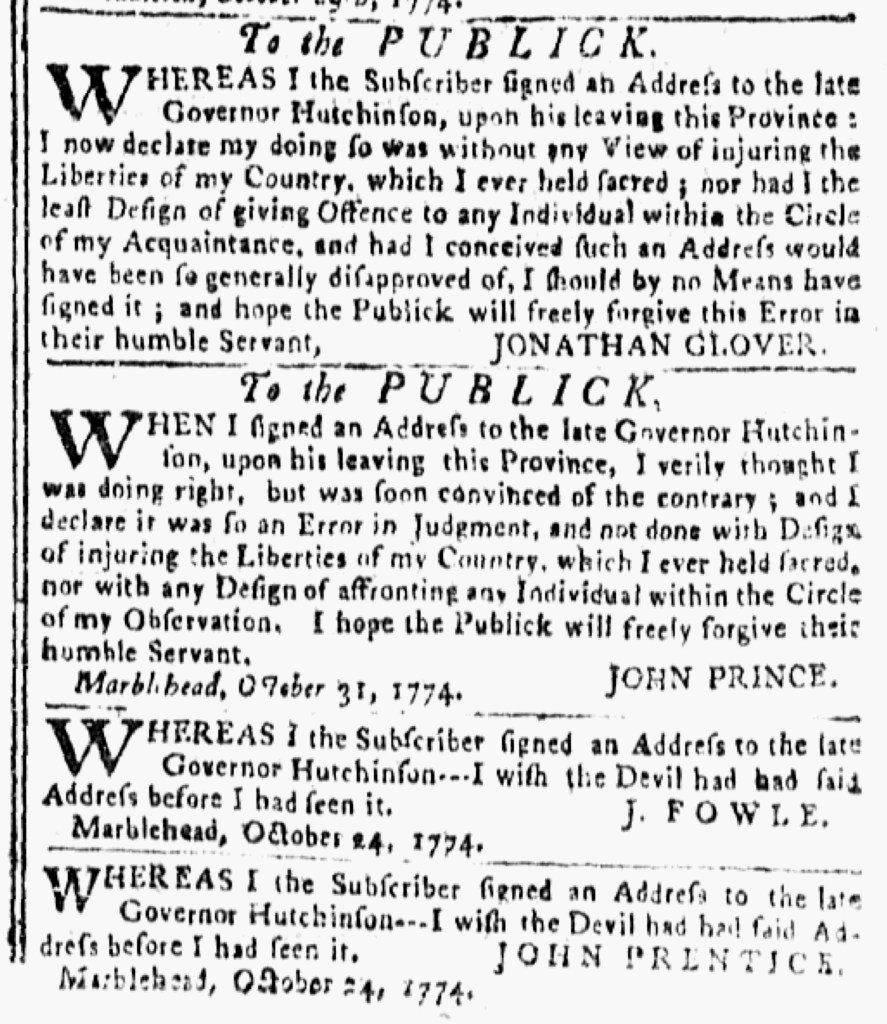

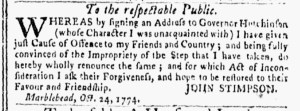

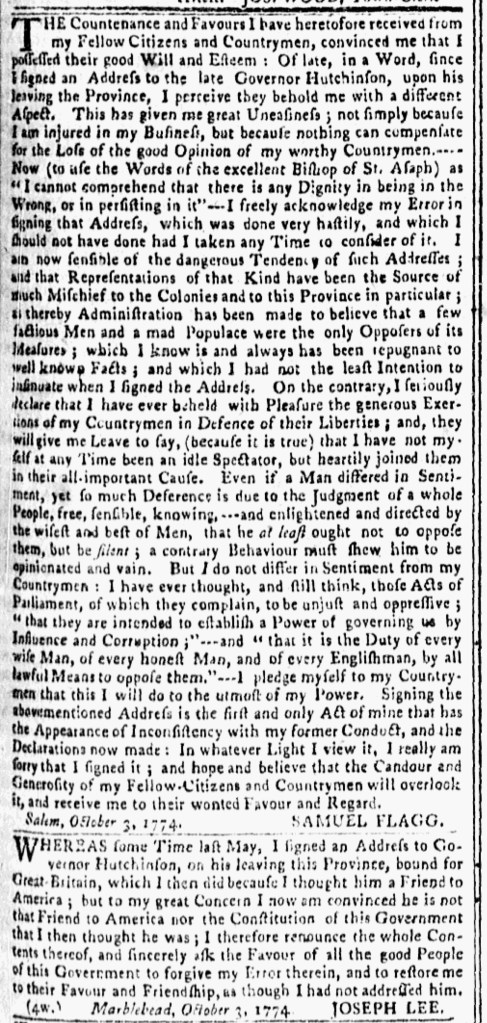

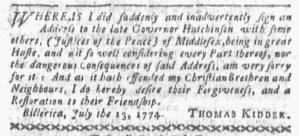

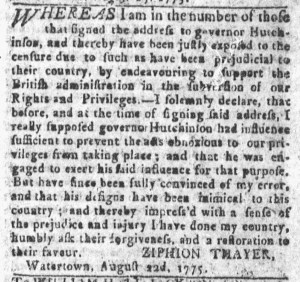

It was yet another apology for signing an address to Thomas Hutchison when General Thomas Gage replaced him as governor of Massachusetts and he departed for England. This time Ziphion Thayer lamented his error in an advertisement in the August 28, 1775, edition of the Boston-Gazette, published in Watertown as the siege of Boston continued. Thayer acknowledged that he signed the address and “thereby have been justly exposed to the censure due to such as have been prejudicial to their country, by endeavouring to support the British administration in the subversion of our Rights and Privileges.” As others indicated in their own apology-advertisements, signing the address came with consequences. The “censure” that Thayer experienced likely included other colonizers refusing to engage with him socially or in business.

For a time, many signatories who published apology-advertisements claimed that they had affixed their names in haste without reading carefully or fully considering the full implications of the address. More recently, however, others explained that they signed because they thought at the time that Hutchinson had the power to protect them from the “Vengeance of the British Ministry” and an inclination to advocate for American liberties. “I solemnly declare, that before, and at the time of signing said address,” Thayer claimed, “I really supposed governor Hutchinson had influence sufficient to prevent the acts obnoxious to our privileges from taking place; and that he was engaged to exert his said influence for that purpose.”

Things certainly did not work out that way, leading Thayer to declare that he had “since been fully convinced of my error” and now realized that Hutchinson’s designs “have been inimical to this country.” Did Thayer have an authentic conversion? Or did he merely say what others wanted to hear so he could return to his former standing in his community? William Huntting Howell contends that the authenticity of such apology-advertisements mattered much less to Patriots than the “rote expression of allegiance” in the public prints.[1] Thayer asserted that he became “impress’d with a sense of the prejudice and injury I have done my country” and, accordingly, he “humbly ask[ed] their forgiveness, and a restoration to their favour.” Whether or not Thayer truly believed the former, he wanted the latter and likely believed that his apology-advertisement would help convince others to overlook what he had done.

**********

[1] William Huntting Howell, “Entering the Lists: The Politics of Ephemera in Eastern Massachusetts, 1774,” Early American Studies 9, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 215-6.