What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“… to be sold by the Printer hereof.”

Advertisements filled the final column on the third page and the entire last page of the April 9, 1774, edition of the Providence Gazette. They generated significant revenue for John Carter, the printer, yet not all the advertisements were paid notices. Like many other printers, Carter used his newspaper to disseminate his own advertisements. He inserted five of the notices that appeared in that issue.

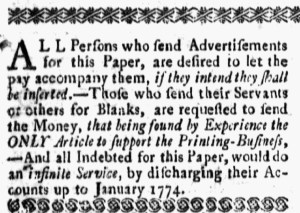

Those advertisements related to a variety of aspects of operating Carter’s printing office “at Shakespear’s Head, in Meeting-Street, near the Court-House.” In one, he called on “ALL Persons indebted for this Gazette one Year, or more” and anyone else indebted to him for other services “to make immediate Payment.” In another, Carter sought a “trusty and well-behaved Lad, about 13 or 14 Years of Age” as “an Apprentice to the Printing Business.” Candidates needed to be able to “read well, and write tolerably.” In yet another, a headline in a larger font than anything else in that issue, even the title of the newspaper in the masthead, proclaimed, “RAGS.” Carter offered the “best Prices … for clean Linen Rags, of any Kind, and old Sail-Cloth, to supply the PAPER MANUFACTORY in Providence.” The printer intended to recycle rags into paper that he would then use to publish subsequent editions of the Providence Gazette.

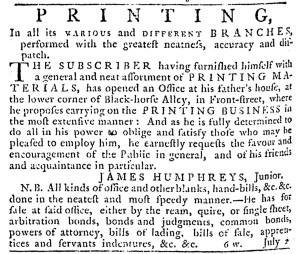

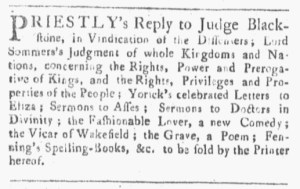

Other advertisements promoted items for sale at the printing office. Most printers also sold books. A few came from their own presses or other colonial presses, but most were imported from England. Carter listed several titles for readers with diverse interests, from “PRIESTLY’s Reply to Judge Blackstone, in Vindication of the Dissenters” to “the Fashionable Lover, a new Comedy” to “the Grave, a Poem” to “Fenning’s Spelling-Books.” An “&c.” (an abbreviation for et cetera) indicated that he stocked many more books, pamphlets, and broadsides. A shorter advertisement stated, “BLANKS of various Kinds to be sold by the Printer hereof.” Carter printed and sold forms for common legal and commercial transactions. Even the colophon doubled as an advertisement, informing readers that “all Manner of Printing-Work is performed with Care and Expedition.”

Carter took advantage of his access to the press to tend to the different parts of operating a busy printing office. While his advertisements did not generate revenue in the same manner as the paid notices placed by merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, estate executors, lottery managers, and others, they supported his business in other ways and some likely resulted in revenue from the sale of books and blanks or the settling of accounts. Collectively, they gave Carter a very visible presence in the pages of the Providence Gazette.