What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Strong and Small Malt Beer and Spruce, by the Barrel.”

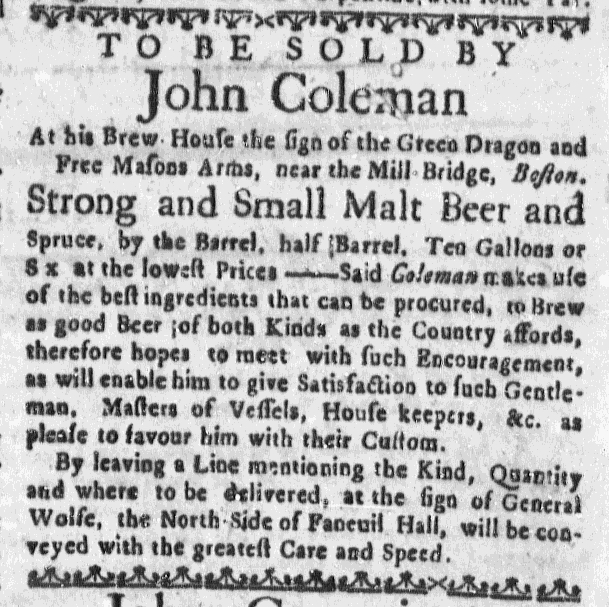

In the fall of 1768 John Coleman advertised the several varieties of beer he sold at “his Brew House [at] the sign of the Green Dragon and Free Masons Arms, near the Mill Bridge” in Boston. He advised “Gentlem[e]n, Masters of Vessels, House keepers” and others that he brewed spruce beer and two sorts of malt beer, strong and small. His spruce beer may or may not have contained alcohol. Many consumers, including “Masters of Vessels,” purchased it as a means of warding off scurvy. His small beer contained less alcohol than strong beer. A safer alternative to water, some customers likely served small beer to children, servants, and other members of their households. Coleman marketed his beers in several quantities – “by the Barrel, half Barrel, Ten Gallons or Six” – and allowed his customers to choose according to their needs.

The brewer made many of the most common appeals that appeared in advertisements throughout the eighteenth century. He made an appeal to price, stating that he sold his beer “at the lowest Prices.” He also made an appeal to quality, stating that he brewed “as good Beer of both Kinds as the Country affords.” His beer was equal to any other produced in the colonies. In another regard, however, Coleman deviated from the marketing strategies deployed in most other advertisements of the era. For the convenience of his customers, he provided delivery service. He concluded with these instructions: “By leaving a Line mentioning the Kind, Quantity and where to be delivered” customers will have their beer “conveyed with the greatest Care and Speed.” Coleman provided an alternate address for placing such orders, “the sign of General Wolfe, the North Side of Faneuil Hall” rather than at “his Brew House.” Presumably customers could have also submitted orders at the latter as well; the additional location compounded the conveniences offered to them.

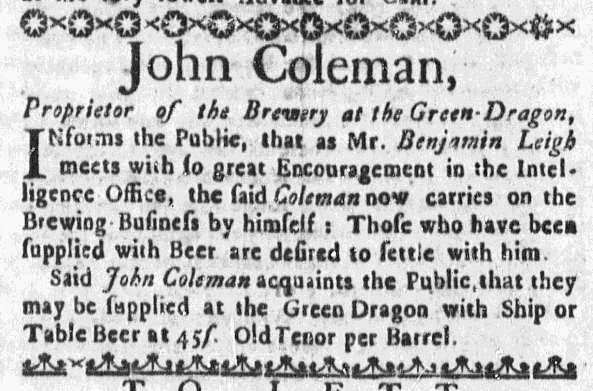

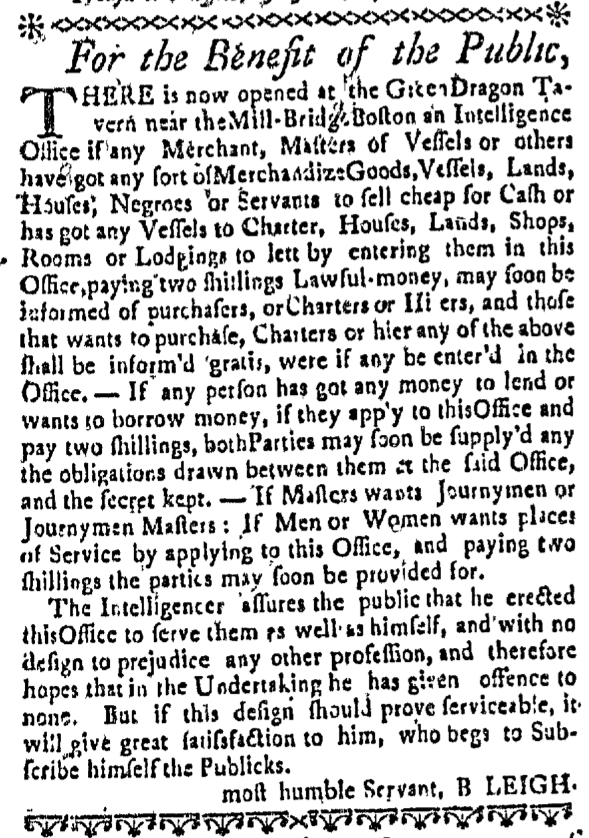

Coleman had previously advertised in the Boston Weekly News-Letter. Just two months earlier he announced that his former partner, Benjamin Leigh, was so busy with his new enterprise running an “Intelligence Office” that Coleman now operated the brewery on his own. He called on prior customers to settle accounts and briefly mentioned the price of a barrel of beer. In this subsequent advertisement, however, he incorporated several new appeals intended to market his beer more effectively. Having assumed sole responsibility for the business, he may have determined that attracting customers demanded greater innovation.