What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A collection of the most elegant swords ever before made in America.”

John Anderson’s call for advertisers to insert notices in the Constitutional Gazette yielded more results. He touted the circulation of his new newspaper in the August 23, 1775, edition, asserting that the “Public will easily perceive the advantage of advertising in the Constitutional Gazette.” Three days later, Abraham Delanoy ran an advertisement for pickled lobsters and fried oysters, adorning it with the woodcut depicting a lobster trap and an oyster cage that accompanied his advertisements in other newspapers. Like printers of other newspapers, Anderson also inserted several advertisements that promoted the goods and services available at his printing office.

For the September 2 edition, other advertisers submitted notices. Roger Haddock and William Malcolm described the contents of a chest stolen from onboard the Thistle on August 30 and offered a reward for apprehending the thief and returning the missing items. Peter Garson and Caleb Hall advertised a house and land at “Peek’s-Kill, on the post-road, within three quarters of a mile of a convenient landing” that they considered “suitable for a merchant, trader, or mechanick.” In collaboration with Mrs. Joyce and other local printers, Anderson once again hawked “JOYCE’s Grand American Balsam,” a patent medicine that alleviated a variety of disorders. He also continued advertising a pamphlet, “Self defensive WAR lawful.”

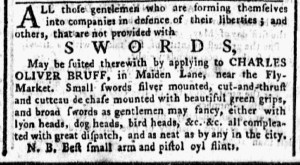

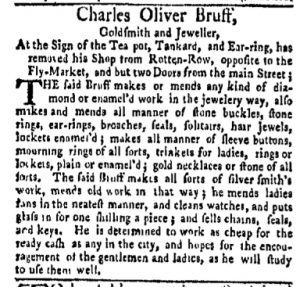

In addition, Charles Oliver Bruff, a goldsmith and jeweler with experience advertising in other newspapers, placed an advertisement for “SWORDS.” Although Delanoy republished copy from his previous advertisements, Bruff generated new copy for his advertisement in the Constitutional Gazette. “Those Gentlemen who are forming themselves into Companies in Defence of their LIBERTIES,” he proclaimed, “that are not provided with SWORDS, May be suited therewith by applying to Charles Oliver Bruff.” Such an appeal kept with the tone of Anderson’s Constitutional Gazette. Bruff presented several options for the pommel, including William Pitt’s head with the motto “Magna Charta and Freedom” and John Wilkes’s head and the motto “Wilkes and Liberty.” Both men had been vocal advocates of American rights in Britain. Bruff was not the first advertiser in the colonies to honor Pitt and Wilkes with commemorative items. The goldsmith and jeweler declared that he stocked “the most elegant swords ever made in America, all manufactured by said BRUFF.” His advertisement fit the times now that hostilities had commenced in Massachusetts and George Washington took command of the Continental Army laying siege to Boston. As Anderson sought to expand advertising in the Constitutional Gazette, Bruff’s advertisement for swords addressed to gentlemen defending “their LIBERTIES” complemented his own advertisement for John Carmichael’s sermon, “Self defensive WAR lawful.”