What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Just published … the following new comedies.”

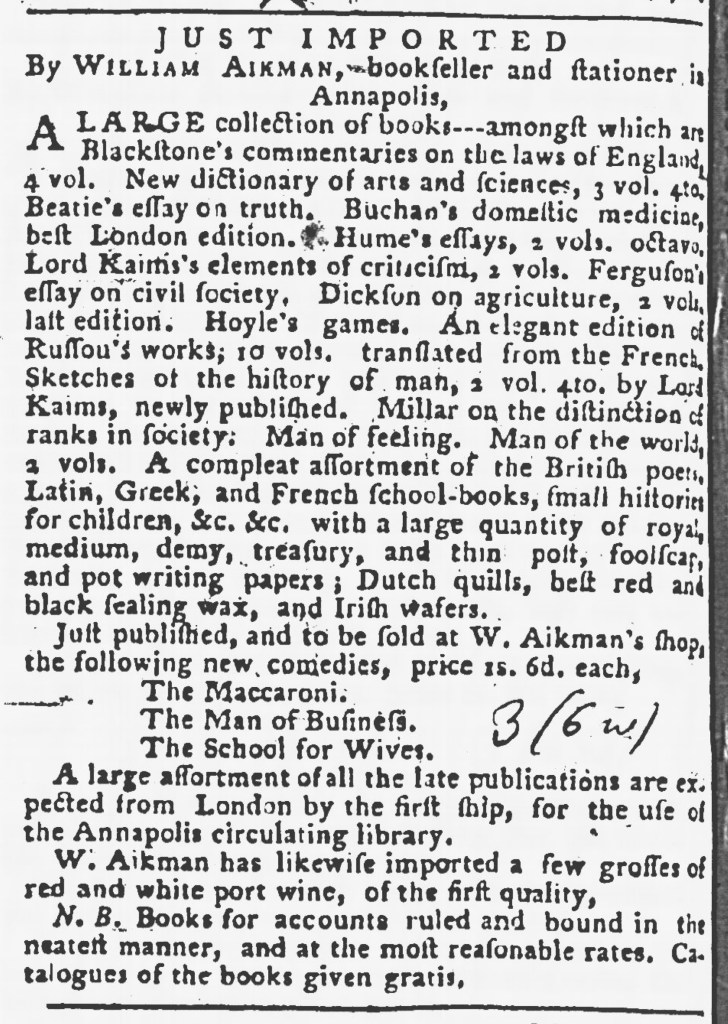

In the spring and summer of 1774, William Aikman, “bookseller and stationer in Annapolis,” advertised a “LARGE collection of books” in the Maryland Gazette. He listed all sorts of titles, including “Blackstone’s commentaries on the laws of England” in four volumes, “Buchan’s domestic medicine, best London edition,” and “Russou’s works, … translated from the French.” In addition, he stocked a variety of books from several genres, ranging from a “compleat assortment of the British poets” to “Latin, Greek, and French school-books” to “small histories for children.” Aikman had something for every reader.

The bookseller also devoted a portion of his advertisement to three “new comedies” that sold for one shilling and six pence each. These works, “Just published,” most likely were reprints that he acquired from John Dunlap in Philadelphia. In 1774, Dunlap printed American editions of Robert Hitchcock’s The Macaroni: A Comedy, as It Is Performed at the Theatre Royal, George Coleman’s The Man of Business: A Comedy: As It is Acted at the Theatre-Royal in Covent-Garden, and Hugh Kelly’s The School for Wives: A Comedy: As It Is Performed at the Theatre-Royal in Drury Lane. Perusing those works gave readers in the colonies, in Philadelphia or Annapolis or anywhere else that Dunlap distributed his reprinted editions, a taste of the theater scene in the cosmopolitan center of the empire.

In addition, Aikman announced that a “large assortment of all the late publications are expected from London by the first ship, for the use of the Annapolis circulating library.” That was another venture that the enterprising bookseller and stationer oversaw. A year earlier, he opened that library and advertised the subscription fees for joining for a month, a quarter, six months, or a year. In the fall of 1773, he advertised that his Annapolis Circulating Library provided delivery service to Baltimore, both a convenience for members there and an attempt to undercut a competing library proposed by a competitor who did not manage to establish a library there.

Overall, Aikman’s advertisement revealed multiple trajectories for producing, distributing, and acquiring books on the eve of the American Revolution. Booksellers received most of their inventory from English printers, though printers in the colonies published both American editions and original works. Those printers worked with printers and booksellers in other towns to exchange, market, and sell books and pamphlets printed in the colonies. For their part, readers could purchase books or join circulating libraries to increase their access to larger libraries than they could afford on their own.