What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Please to make your Cloth suitable … and not expect a Silk Purse to be made of a Sow’s Ear.”

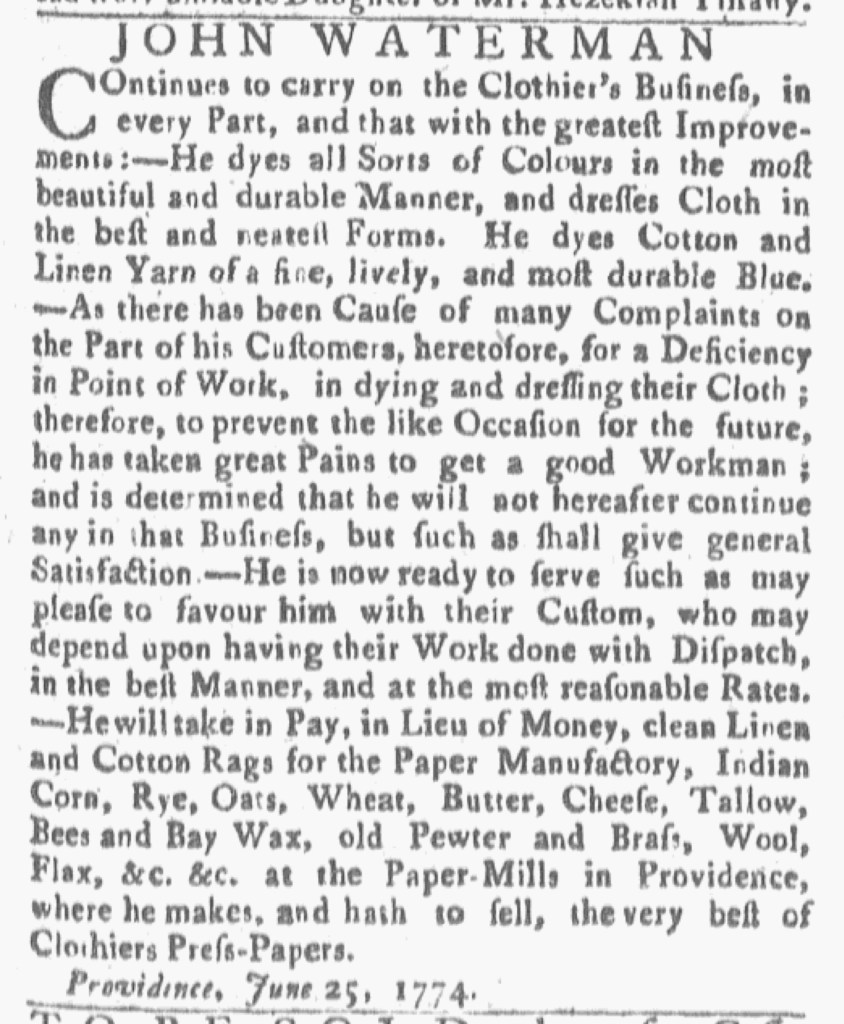

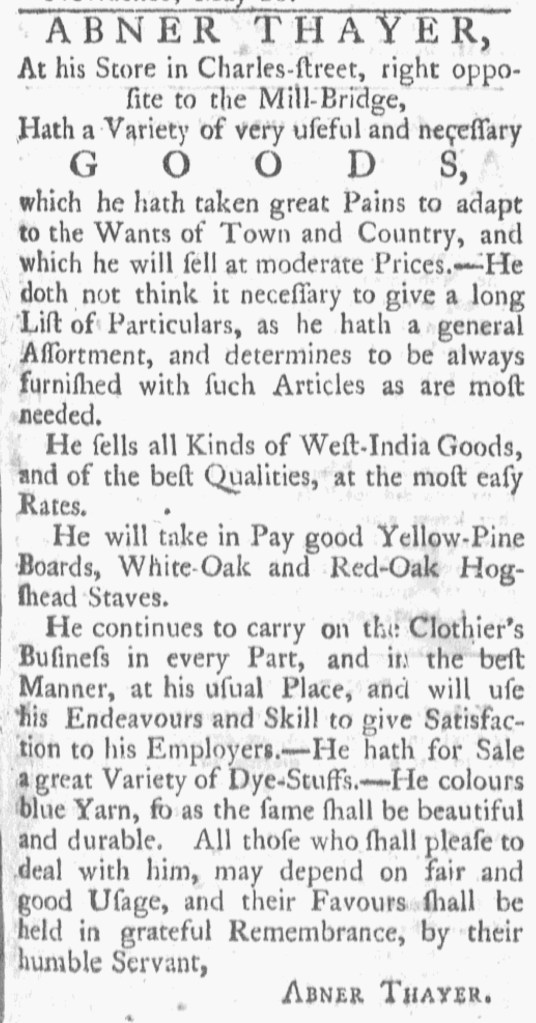

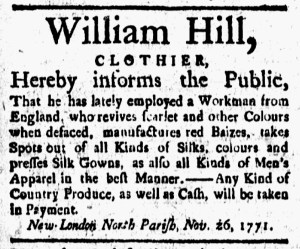

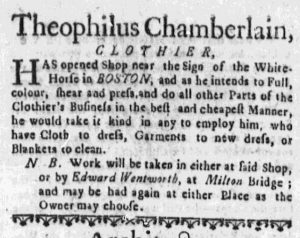

As spring approached in 1775, Nathaniel Wollys, “Silk-Dyer and Clothier,” took to the pages of the Connecticut Gazetteto advise the public that “he carries on the Clothing-Business” in “several Branches.” Those included “fulling, colouring, shearing, pressing and dressing of Bays, Fustian, Ratteen and Bearskin,” dying “Cotton and linnen Yarn blue,” “dy[ing] and dress[ing] Silks of all Kinds,” and “tak[ing] out Colours, Spots or Stains of any Kind.” Colonizers certainly knew the differences among the various textiles Wollys named, even if they are now unfamiliar to most consumers in the twenty-first century. Like other advertisers who provided services, Wollys emphasized both his own engagement with customers, his “Fidelity and Dispatch,” and the quality of his work, done in “the neatest and best Manner.”

However, the fuller appended a lively nota bene that reminded prospective customers to have reasonable expectations for what he could accomplish with the textiles they delivered to his mill for treatment or cleaning. Some feats were beyond the skills of any clothier, no matter how experienced. “Please to make your Cloth suitable for the Work you intend it for,” Wollys bluntly instructed, “and not expect a Silk Purse to be made of a Sow’s Ear.” Perhaps he reacted to customers who had recently expressed displeasure or dissatisfaction with the finished product, seeking to set the terms for new clients before they hired his services. If that was the case, former customers may have given voice to the frustration they experienced as they participated in boycotts of imported fabrics and substituted homespun textiles. While using such cloth became a mark of distinction permeated with political meaning, garments and other items made from homespun were not of the same quality as those made from imported textiles. Even as consumers made sacrifices in support of their political principles, some of Wollys’s customers may have transferred their disappointment in not having access to the same finery to the clothier who processed the cloth that they increasingly incorporated into their everyday routines. Wollys could accomplish a lot when he treated cloth “in the neatest and best Manner,” yet clients also needed to be realistic about the anticipated outcomes.