What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250years ago today?

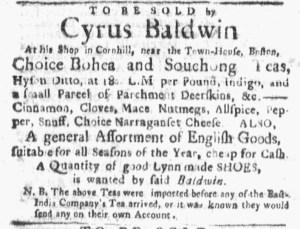

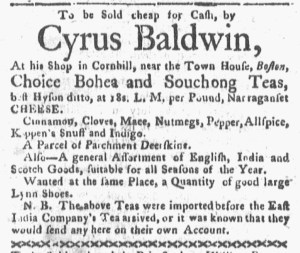

“The above Teas were imported before any of the East-India Company’s Tea arrive, or it was known they would send any on their own Account.”

Cyrus Baldwin advertised “Choice Bohea and Souchong Tea” in the December 20, 1773, edition of the Boston Evening-Post, the first issue published following the protest now known as the Boston Tea Party. In an effort to convince both prospective customers and the general public that he traded in good faith, he appended a nota bene to assert that his teas “were imported before any of the East-India Company’s Tea arrive, or it was known they would send any on their own Account.” Three days later, he ran a similar advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy. That notice included new merchandise, but it still listed “CHOICE Bohea and Souchong Teas” and concluded with the same nota bene. As the politics of tea became a main topic of discussion, in town meetings, in the press, in everyday conversation, did not decide to discontinue his advertisements presenting tea for sale at his shop in Boston.

On December 27, Baldwin once again advertised in the Boston Evening-Post, replacing his advertisement from the previous issue with the one from the Massachusetts Spy. In addition, that advertisement, complete with the nota bene, also ran in the Boston-Gazette on December 27. Over the course of several days, Baldwin inserted it in three of the five newspapers published in Boston at the time. Notably, neither Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy, nor Benjamin Edes and John Gill, the printers of the Boston-Gazette, rejected the advertisement, though they had earned reputations as the printers who most vociferously advocated for the patriot cause and critiqued Parliament and colonial officials. Did their willingness to publish the advertisement serve as tacit endorsement of the rationale Baldwin offered to justify selling his tea? Maybe not. The printers may have been too busy participating in events as they unfolded after the Boston Tea Party and gathering news from near and far that they did not scrutinize the contents of all the advertisements submitted to their printing offices. After all, other merchants and shopkeepers continued to advertise tea in the Boston-Gazette and the Massachusetts Spy. The printers may not have examined each advertisement closely to spot tea among the lists of merchandise. They might have also been satisfied, at least for the moment, because they knew any tea sold by Baldwin and others had not been acquired via the problematic shipments that ended up in the harbor rather than in shops and stores.

As colonizers, including “Venders of Tea,” debated what to do next following the Boston Tea Party, they did not immediately cease advertising, buying, selling, and drinking tea. Following strategies that they adopted in response to the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts, they eventually devised nonimportation and consumption agreements. Loyalists like Peter Oliver accused patriots, especially women, of cheating on those agreements. Such indiscretions would have been a continuation of the flexibility toward tea exhibited in newspaper advertisements published in the days immediately after the Boston Tea Party.