What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

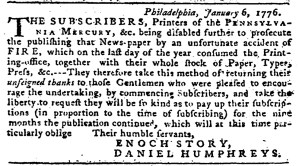

“Disabled further to prosecute the publishing that News-paper by an unfortunate accident of FIRE.”

As the imperial crisis intensified, Enoch Story and Daniel Humphreys launched the Pennsylvania Mercury (quickly renamed Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury) on April 7, 1775. That newspaper joined two others founded earlier in the year, the Pennsylvania Evening Post on January 24 and the Pennsylvania Ledger on January 28, as well as Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, the Pennsylvania Gazette, the Pennsylvania Journal, and the Wochentliche Pennsylvanische Staatsbote. During the first four months of 1775, Philadelphia surpassed Boston in terms of the number of newspapers printed there. With the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord on April 19 and the ensuing siege of Boston, several of Boston’s newspapers ceased publication or relocated to other towns.

Yet Boston was not the only major port city that saw one of its newspapers cease publication during the first year of the Revolutionary War. Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury lasted less than a year, though disruptions caused by the war did not lead to its demise. Unfortunately, “an unfortunate accident of FIRE … consumed the Printing-office, together with their whole Stock of Paper, Types, Press,” and other equipment on December 31. The situation did not leave any possibility for the partners to recover and eventually resume publication. “[B]eing disabled further to prosecute the publishing [of] that News-paper,” they announced in an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, they instead expressed “their unfeigned thanks” to the subscribers who had supported the venture and requested that they “will be so kind as to pay up their subscriptions (in proportion to the time of subscribing) for the nine months the publication continued.” In other words, they expected customers to make prorated payments based on the number of issues they received. Humphreys eventually tried again, but not until after the Revolutionary War. On August 20, 1784, he commenced publishing a new Pennsylvania Mercury.

Even with the loss of Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury, Philadelphia still had more newspapers than any other city or town in the colonies. As the war continued, not all of them survived. Some closed permanently while others moved to other towns or suspended publication during the British occupation of Philadelphia. Yet, as the “unfortunate accident of FIRE” at Story and Humphreys’s printing office demonstrated, disruptions caused by the war were not the only dangers that forced newspapers to fold.