What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“WATCHES … Advice to those who are about to buy, sell or exchange.”

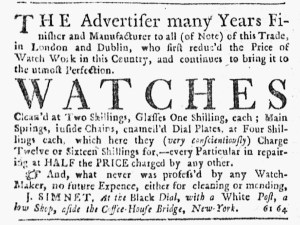

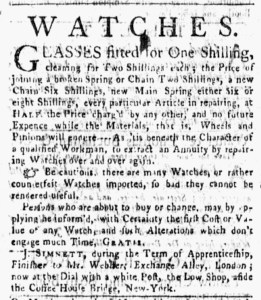

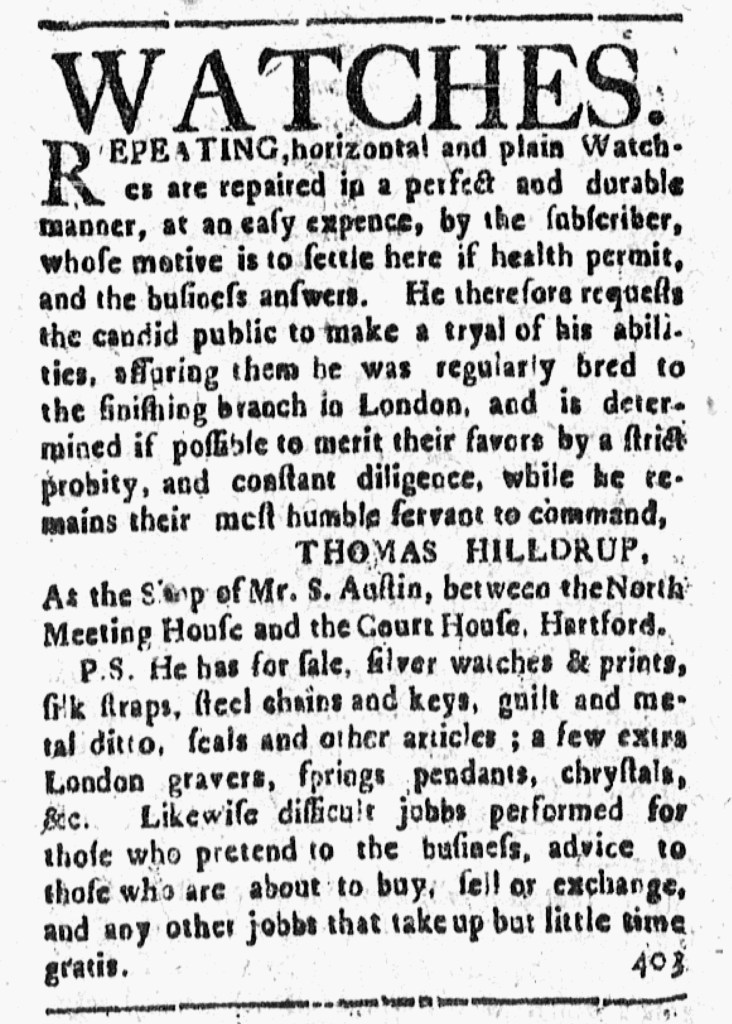

When Thomas Hilldrup arrived in Hartford in the fall of 1772, he commenced an advertising campaign in hopes to introduce himself to prospective customers who needed their watches repaired. He first advertised in the September 15 edition of the Connecticut Courant. That notice ran for three weeks. On October 13, he published a slightly revised advertisement, one that appeared in every issue, except November 10, throughout the remainder of the year. Although many advertisers ran notices for only three or four weeks, the standard minimum duration in the fee structures devised by printers, Hilldrup had good reason to repeat his advertisement for months. He intended to remain in Hartford “if health permit[s], and the business answers.” If he could not attract enough customers to make a living, then he would move on to another town.

Hoping to remain in Hartford, he asked prospective customers “to make a trial of his abilities” to see for themselves how well he repaired watches. Satisfied customers would boost his reputation in the local market, but generating word-of-mouth recommendations would take some time. For the moment, he relied on giving his credentials, a strategy often adopted by artisans, including watchmakers, who migrated from England. Hilldrup asserted that he “was regularly bred” or trained “to the [watch] finishing branch in London.” Accordingly, he had the skills “to merit [prospective customers’] favors” or business, aided by his “strict probity, and constant diligence.” In addition, Hilldrup offered ancillary services in hopes of drawing customers into his shop. He sold silver watches, steel chains, watch keys, and other merchandise. He also provided “advice to those who are about to buy, sell or exchange” watches, giving expert guidance based on his professional experience. Hilldrup concluded his advertisement with an offer that he likely hoped prospective customers would find too good to dismiss. He stated that he did “any other jobbs that take up but little time gratis.” Doing small jobs for free allowed the watchmaker to cultivate relationships with customers who might then feel inclined or even obligated to spend more money in his shop.

By running an advertisement with the headline “WATCHES” in a large font larger than the size of the title of the newspaper in the masthead, Hilldrup aimed to make his new enterprise visible to prospective customers in and near Hartford. He included several standard appeals, such as promising low prices and noting his training in London, while also promoting ancillary services to convince readers to give him a chance.