What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“A NIGHT SCHOOL.”

“FRENCH ACADEMY.”

Two advertisements in the November 4, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post and its supplement offered opportunities for learning and self-improvement. In the first notice, Matthew Maguire announced that he had opened a “NIGHT SCHOOL” for “youth of both sexes.” The curriculum included “the various branches of READING, WRITING and ARITHMETIC,” subjects that both boys and girls typically learned. Maguire also indicated that he taught “ACCOMPTS [or accounts] in all their different forms, after the latest and most approved methods,” though he did not mention whether he reserved that subject for male students. Learning how to keep daybooks and ledgers may have been useful for some of the girls and young women who attended Maguire’s school, especially those that attended in the evening because they assisted in running the family business during the day. Maguire also provided lessons during the day “as usual,” but he specified in a nota bene that he continued admitting “Young ladies only.” In addition to giving female students a homosocial setting with fewer chances of disruptions, he may he reasoned that most boys and young men who would attend the school he kept in his house in Carter’s Alley did indeed have apprenticeships and other responsibilities during the day.

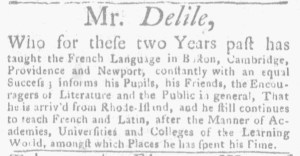

In the other advertisement, Francis Daymon, “MASTER of the French and Latin Languages” and “LIBRARIAN of the Philadelphia Public Library” (or the Library Company of Philadelphia), advised prospective pupils that he “HAS opened his FRENCH ACADEMY for the winter season.” Classes began “punctually at seven o’clock every evening (Saturday excepted),” though it went without saying that he did not give lessons on Sundays. Daymon delivered lessons “in the Library Room in Carpenters Hall,” the Library Company having moved to the second floor of that building from the Pennsylvania State House when it was completed in 1773. He presumably admitted students of both sexes since he did not indicate otherwise in his advertisement. He did note that “Ladies and Gentlemen may be instructed at their places of abode as usual,” an arrangement that allowed his pupils or their parents to determine who would be present. Unlike Maguire, Daymon offered private lessons, likely setting rates for his students for the convenience of learning in their homes accordingly.

While some of the students who learned reading, writing, arithmetic, and accounts from Maguire could have also sought out French lessons from Daymon, the two schoolmasters cultivated different clienteles. Maguire emphasized basic skills for everyday use by a wide range of colonizers, while Daymon’s French lessons appealed to genteel residents of Philadelphia and those aspiring to gentility. With the Continental Association, a nonimportation and nonconsumption agreement, in effect, discourses about fashion had shifted. Learning French gave some colonizers an alternate way to assert their status.