What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

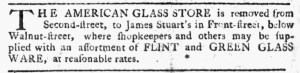

“THE AMERICAN GLASS STORE is removed from Second-street.”

The advertisement consisted of only five lines in the October 24, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, yet it spoke volumes about the current events. “THE AMERICAN GLASS STORE,” the notice informed the public, “is removed from Second-street, to James Stuart’s in Front-street, below Walnut-street, where shopkeepers and others may be supplied with an assortment of FLINT and GREEN GLASS WARE, at reasonable rates.” It was one of many advertisements that presented opportunities for colonizers to “Buy American” during the imperial crisis that eventually became a war for independence.

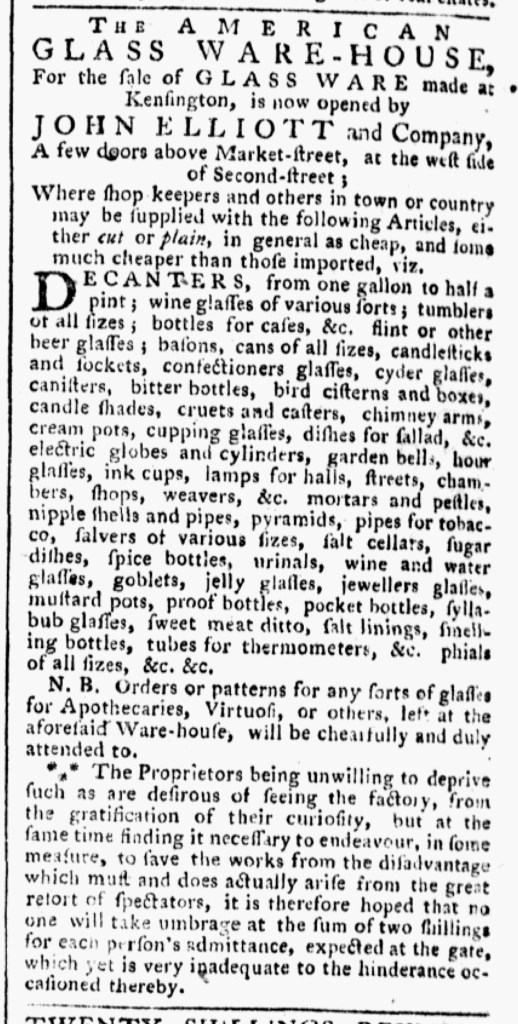

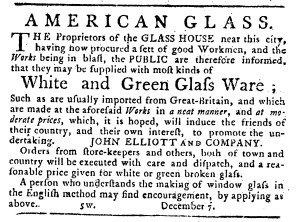

On several occasions, supporters of the American cause participated in boycotts in hopes of using their participation in the marketplace as leverage to achieve political ends. They organized nonimportation agreements in response to the Stamp Act in 1765 and in response to the duties levied on certain imported goods, including glass, in the Townshend Acts in the late 1760s. Simultaneously, they called for “domestic manufactures” or goods produced in the colonies as alternatives to imported wares. In August 1769, Richard Wistar advertised products from his “GLASS-WORKS,” items “of American manufactory” produced in Pennsylvania, “consequently clear of the duties the Americans so justly complain of.” The most extensive and coordinated boycott, the Continental Association devised by the First Continental Congress in response to the Coercive Acts, went into effect on December 1, 1774. Within a week, the “Proprietors of the GLASS HOUSE near this city,” Philadelphia, advertised “White and Green Glass Ware; Such as are usually imported from Great-Britain.” The proprietors accepted orders from “store-keepers and others, both of town and country.” As the imperial crisis intensified, savvy entrepreneurs opened an “AMERICAN GLASS STORE” in Philadelphia, an establishment that specialized in glassware produced locally. The Continental Association specified that colonizers “will, in our several Stations, encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts, and the Manufactures of this Country.” Local producers of glassware delivered, but they needed retailers and consumers to do their part as well. The brief advertisement in the Pennsylvania Evening Post let shopkeepers and other customers, all of them very much aware of the events of the last decade, know where they could express their political principles by purchasing American glassware.