Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

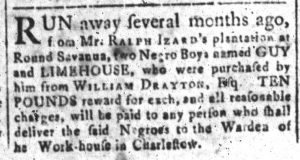

“RUN away … two Negro Boys named GUY and LIMEHOUSE.”

American colonists engaged in a variety of resistance activities in response to new legislation passed by Parliament with the intention of better regulating the vast British Empire in the years after the Seven Years War concluded. Colonial legislatures passed resolutions asserting the rights of American and submitted petitions encouraging Parliament to reconsider. Merchants and shopkeepers organized nonimportation agreements, disrupting commerce as a means of achieving political goals. Extending those efforts, consumers boycotted goods imported from Britain. Many colonists also expressed their political views by participating in public demonstrations, some of them culminating in violence. The colonial press chronicled all of these efforts, contributing to the creation of an imagined community from New England to Georgia. Print culture played an important role in creating a sense of a common cause for many colonists.

Yet white colonists were not the only ones thinking about liberty and those were not the only means of seeking freedom. Enslaved Africans and African Americans did not need newspaper reports about petitions, nonimportation agreements, and public demonstrations to inform them of the ideals of liberty and the meaning of freedom. Many engaged in their own acts of resistance, seizing their own liberty by escaping from bondage. Such was the case for “two Negro Boys named GUY and LIMEHOUSE.” Late in the winter or early in the spring of 1769, these two young men decided to make their escape from Ralph Izard’s plantation. For weeks, Izard ran advertisements in South Carolina’s newspapers, including in the July 4, 1769, edition of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette. He offered a reward of ten pounds each for the capture and return of Guy and Limehouse, instructing that they should be delivered “to the Warden of [t]he Work-house in Charlestow[n].”

Other than their names (presumably names bestowed on the young men by their enslavers), Izard provided little information about the young men. He described them as “Boys,” but did not offer even an approximation of their ages. Izard indicated that he had purchased Guy and Limehouse from William Drayton, but did not report how much time had elapsed between that transaction and their escape. For at least a couple of months, the young men experienced freedom, though they likely never felt secure. Guy and Limehouse’s stories, as told by Izard, were exceptionally truncated compared to the stories they would have told about themselves. Still, their determination to free themselves demonstrates that the spirit of liberty was not confined to white colonists aggrieved over the actions of Parliament.

That spirit of liberty, however, existed in stark contrast to the realities of enslavement during the imperial crisis, throughout the American Revolution, and beyond. Advertisements for enslaved men, women, and children who attempted to seize their own liberty highlight that paradox of the American founding. Many historians address the tension between liberty and enslavement in the era of the American Revolution, both in projects intended mainly for their colleagues in the academy and projects intended to engage the general public. On July 4, as Americans celebrate Independence Day, the Adverts 250 Project seeks to add to that conversation by presenting the stories of enslaved people who made their escape from bondage at the same time that white colonists protested for their rights and freedom from figurative enslavement to Parliament. In addition to the stories of Guy and Limehouse, learn more about Caesar, advertised in the Providence Gazette on July 4, 1767, and Harry, advertised in the Pennsylvania Chronicle on July 4, 1768. Celebrations of Independence Day should acknowledge the complexity of American history and commemorate the courage and conviction of enslaved people who pursued their own means of achieving freedom in an era of revolutionary fervor.