Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

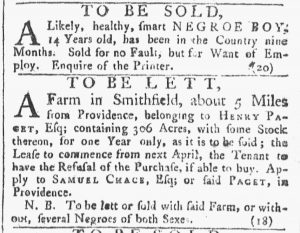

“TO BE SOLD, A Likely, healthy, smart, NEGROE BOY.”

The Slavery Adverts 250 Project chronicles how newspaper advertising contributed to the perpetuation of slavery during the era of the American Revolution. Every day the project identifies, remediates, and republishes advertisements about enslaved men, women, and children originally published in British mainland North America 250 years ago that day. In so doing, the project seeks to undo the forced forgetting of enslavement throughout the thirteen colonies that became the United States, especially northern colonies that became free states through immediate or gradual emancipation in the decades following the Revolution. Newspaper advertisements demonstrate that slavery was part of everyday life in colonies from New England to Georgia during the first three quarters of the eighteenth century. Readers regularly encountered notices about enslaved people in the public prints, just as they encountered enslaved people in public and private spaces.

Consider the March 3, 1770 edition of the Providence Gazette. It contained two advertisements that sought to sell enslaved men, women, and children. The first announced that an unnamed enslaver wished to sell a “Likely, healthy, smart NEGROE BOY” who had been “in the Country nine Months.” Presumably he survived the Middle Passage from Africa or transshipment from the Caribbean to arrive in Rhode Island in the summer of 1769. The anonymous advertiser assured prospective purchasers that the enslaved youth was “Sold for no Fault” other than “Want of Employ.” In other words, the enslaver did not have enough tasks to keep the “NEGROE BOY” busy and wished to recoup the investment. The second notice focused primarily on a farm “TO BE LETT” and eventually sold in Smithfield. Henry Pacet advertised more than the farm “with some Stock thereon.” In a nota bene, a device deployed to draw particular attention to important information, he announced that he would rent or sell “several Negroes of both Sexes,” if tenants or purchasers wished. They need not have been part of the deal. Pacet and prospective buyers would determine whether any of the enslaved men and women would remain on the farm. Those men and women, reduced to commodities, did not have a say.

Along with an array of other sources, newspaper advertisements demonstrate that slavery was not merely a southern phenomenon. Enslaved people lived and labored in Rhode Island and elsewhere in New England in the era of the American Revolution. Although historians and other scholars are well aware of their presence, too often the general public has “forgotten,” perhaps all too conveniently, that enslaved people were part of the fabric of everyday life and commerce in New England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.