What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Illustrated with a beautiful Plan of Boston, and the Provincial Camp.”

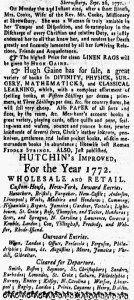

When fall arrived, it was time to market almanacs for the coming year. It was an annual ritual in American newspapers from New England to Georgia. Hugh Gaine, the printer of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, began advertising “HUTCHIN’s Improv’d: BEING AN ALMANACK … For the Year of our LORD 1776” on September 18, 1775, and then inserted his extensive notice in subsequent issues. The almanac’s contents included the usual astronomical data, such as “Length of Days and Nights” as well as a schedule of the courts, a description of roads to other cities and towns, and “useful Tables, chronological Observations and entertaining Remarks.” Gaine enumerated thirty-one of those items, such as a “Very comical, humorous, and entertaining Adventure of a young LADY that used to walk in her sleep,” an essay on the “evil Consequences of Sloth and Idleness,” and a “Method for destroying Caterpillars on Trees.”

If all of that was not enough to entice customers, Gaine made sure that they knew that the almanac was “Illustrated with a beautiful Plan of Boston, and the Provincial Camp.” That proclamation led the advertisement, appearing immediately above the title of the almanac. Gaine then devoted the greatest amount of space to describing the map: “13. A very neat Plan of the Town of Boston, shewing at one View, the Provincial Camp, Boston Neck, Fortification, Commons, Battery, Magazines, Charlestown Ferry, Mill Pond, Fort Hill, Corps Hill, Liberty Tree, Windmill Point, South Battery, Long Wharf, Island Wharf, Hancock’s [Wharf], Charlestown, Bunker’s Hill, Winter Hill, Cobble Hill, Forts, Prospect Hill, Provincial Lines, Lower Fort, Upper [Fort], Main Guard, Cambridge College, Charles River, Pierpont’s Mill, Fascine Battery, Roxbury Hill Lines, General Gage’s Lines, Dorchester Hill and Point, and Mystick River.” As the siege of Boston continued, Daine realized that colonizers in Boston would be interested in supplementing what they read in newspapers and heard from others with a map that would help them envision and better understand recent events.

What was the source for the map? According to the catalog description for the almanac by PBA Galleries, Auctioneers and Appraisers, the map, “titled a ‘Plan of Boston,’ details Boston’s Shawmut Peninsula and with a smaller inset of the greater Boston area. Both maps appear to be based on the ‘New and Correct Plan of the Town of Boston and Provincial Camp,’ which appeared in the Pennsylvania Magazine for July, 1775.” The image that Aitken marketed to spur magazine sales found its way into another periodical publication. Another printer used it to generate demand for an item produced on his press.

Gaine also listed “11. The whole Process of making SALT PETRE, recommended by the Hon. The Continental Congress, for the making of which there is a Bounty now given both in this and the neighbouring Provinces” and “12. The Method of making Gun-Powder, which at this Juncture may be carried into Execution in a small Way, by almost every Framer in his own Habitation.” The auction catalog further clarifies that the almanac contains “the Resolution of Congress, July 28, 1775 on the necessity of making gunpowder in the colonies, signed in print by John Hancock, with a recipe for gunpowder on the reverse of the map.” More than ever, current events played a part in compiling the contents and then marketing almanacs.