What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

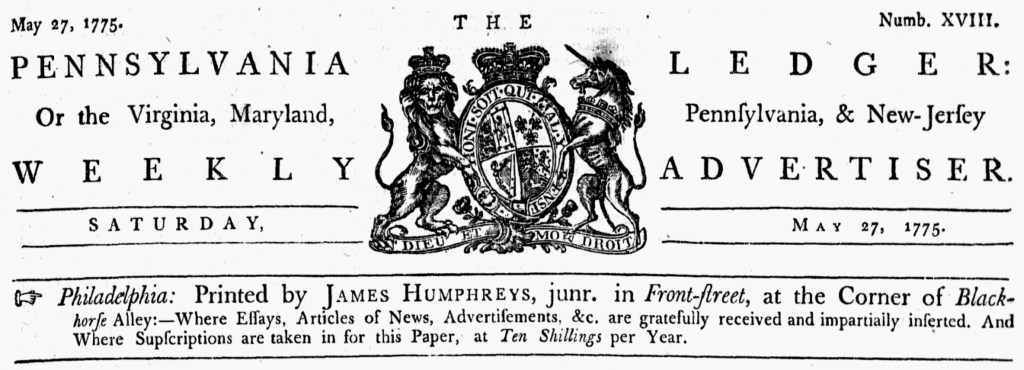

“Essays, Articles of News, Advertisements, &c. are gratefully received and impartially inserted.”

Among newspapers published during the era of the American Revolution, those that included a colophon usually featured it at the bottom of the final page. A few, including the Pennsylvania Ledger, incorporated the colophon into the masthead. James Humphreys, Jr., the printer, also used the colophon as a perpetual advertisement for subscriptions and advertisements. After all, the full title of the newspaper was the Pennsylvania Ledger: Or the Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, & New Jersey Weekly Advertiser. Accordingly, the colophon gave more than just place of publication and the name of the printer (“Philadelphia: Printed by JAMES HUMPHREYS, junr. in Front-street, at the Corner of Black-horse Alley”); it also informed readers that “Essays, Articles of News, Advertisements, &c. are gratefully received and impartially inserted” and “Subscriptions are taken in for this Paper, at Ten Shillings per Year.” The enhanced colophon did not, however, give prices for advertising, though Humphreys stated that he set “the same terms as is usual with the other papers in the city” in the subscription proposals he distributed in January 1775.

What did Humphreys mean when he declared that he “impartially inserted” essays (or editorials), news, and advertisements? In the proposals t, he asserted that “a number of worthy and reputable Gentlemen” in Philadelphia had encouraged him “to establish a Free and Impartial NEWS PAPER, open to All, and influenced by None.” Furthermore, he proclaimed that he was “determined to act on the most impartial principles, and not render himself liable to be influenced by any party whatever.” Such idealism stood in stark contrast to the partisanship of most newspapers as the imperial crisis intensified. Humphreys’s determination to print essays and news from various perspectives amounted to sufficient proof for many Patriots that the printer was a Loyalist since he did not uniformly promote the American cause. Decades later, Isaiah Thomas, the patriot printer who published the Massachusetts Spy at the same time Humphreys published the Pennsylvania Ledger, took a more evenhanded approach in his History of Printing of America: “The publisher announced his intention to conduct his paper with political impartiality; and perhaps, in times more tranquil than those in which it appeared, he might have succeeded in his plan. … The impartiality of the Ledger did not comport with the temper of the times.”[1] Thomas seemed to consider Humphreys’s commitment to freedom of the press authentic rather than a rationalization for printing Loyalist views. He was not so kind in his descriptions of other printers whose politics did not align with his own.

Still, the “temper of the times” likely prompted Humphreys to adjust his own advertising for political pamphlets available at his printing office. When it came to “impartially insert[ing]” advertisements submitted by others, he gave assurances that he neither took an editorial stance when it came to the information they disseminated nor gave some more prominent placement on the page than others. He did not rank newspapers notices but instead gave advertisers equal access to his press.

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 439-440.