What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Proprietors being unwilling to deprive such as are desirous of seeing the factory, from the gratification of their curiosity.”

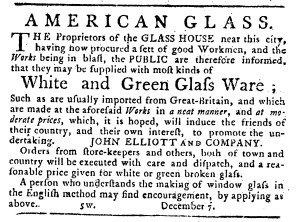

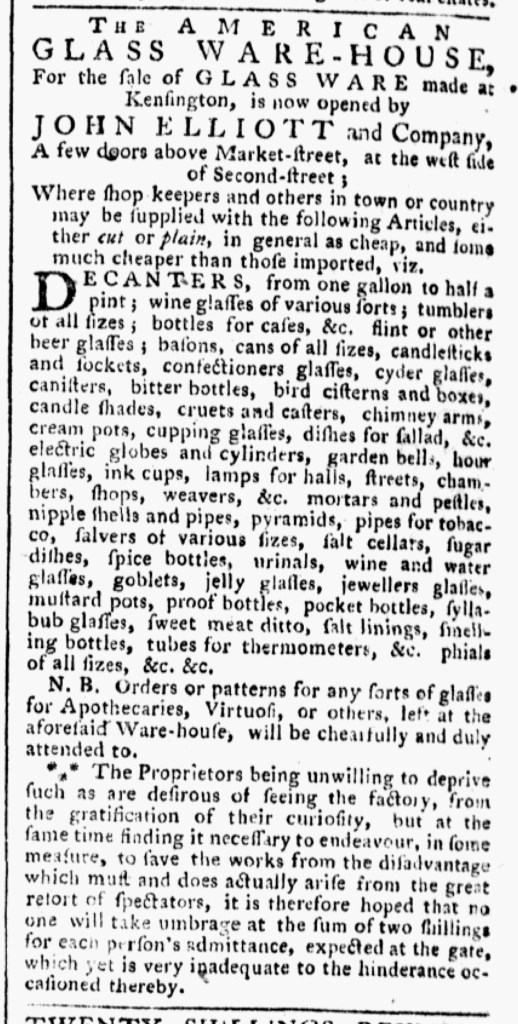

John Elliott and Company advertised items made at the “AMERICAN GLASS WARE-HOUSE” in Kensington, Philadelphia, as soon as the Continental Association went into effect in December 1774. Nearly four months later, the company ran another advertisement that listed a variety of glassware – including “wine glasses of various sorts,” “tumblers of all sizes,” “hour glasses,” “tubes for thermometers,” “mustard pots,” and “lamps for halls, streets, chambers, shops, [and] weavers” – that “shop keepers and others in town or country” could purchase “as cheap [as] those imported.” Some items were “much cheaper.” Colonizers who abided by the nonimportation agreement did not have to pay more to acquire glassware made in the colonies; instead, they got a bargain! Elliott and Company also informed apothecaries and others that they accepted orders and would follow patterns “left at the aforesaid Ware-house.”

Yet this enterprise did more than manufacture glassware. Elliott and Company’s operation became a destination for the curious who wanted to witness the production of “AMERICAN GLASS” for themselves. That had the potential to become disruptive, so the proprietors devoted the final paragraph of their advertisement to instructions for visiting. They explained that they struck a compromise, “being unwilling to deprive such as are desirous of seeing the factory, from the gratification of their curiosity, but at the same time finding it necessary to endeavour, in some measure, to save the works from the disadvantage which must and does actually arise from the great resort of spectators.” Accordingly, Elliott and Company charged “two shillings for each person’s admittance, expected at the gate.” Even that fee, they claimed, “is very inadequate to the hinderance occasioned thereby,” yet, once again, the company offered a bargain. In the process, Elliott and Company monetized visits to their production facility. Perhaps it had not been as popular a destination as they implied. Perhaps they exaggerated in hopes of drumming up interest in such a novelty, especially as the imperial crisis intensified and the Continental Association became even more meaningful to many colonizers. An advertisement with instructions for visiting the factory, no matter how many people had previously been there, gave readers ideas about an outing they could make themselves. Attracting visitors to see the works, after all, would likely translate into additional sales.