What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

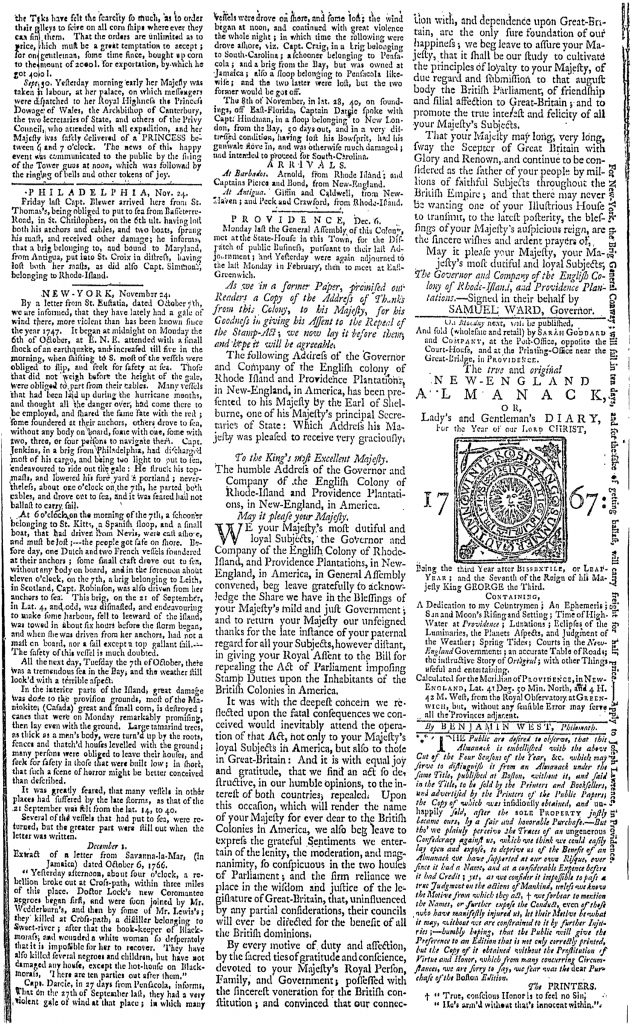

“For New-York, the Brig General Conway; will sail in ten days, and for the sake of getting ballast, will carry freight for half price.”

More than any other printers who published newspapers in 1766, Mary Goddard and Company experimented with layout and graphic design for advertising. In collaboration with several shopkeepers, Goddard and Company mixed genres, placing advertisements that otherwise could have been separately printed and distributed as trade cards within several issues of the Providence Gazette during the summer and fall of 1766. Next, the printers continued producing hybrid publications with issues that featured full-page advertisements, effectively giving over the final page to what otherwise could have been an advertising broadside had it been produced separately.

For those efforts, Goddard and Company emphasized the size of the advertisements that appeared in the pages of the Providence Gazette. Today’s advertisement, however, was relatively short and took up little space on the page. What distinguished it from others was its position within the December 6, 1766, issue. It appeared on the third of four pages, running alongside, but perpendicular to, the column on the far right. It ran in the blank space usually reserved for the margin, making it the last text item readers would have seen when scanning the open pages of the newspaper from left to right.

This advertisement occupied space where text usually did not intrude, which would have encouraged curiosity among readers. Three columns appeared on each page of the Providence Gazette, all of them separated by sufficient white space to make them easily distinguishable from those on either side. This advertisement printed perpendicularly in the margin, however, did not have white space on its left. Instead, it was closely nestled next to the conclusion of a news article and an advertisement for the New-England Almanack. This format served both to hide and highlight the advertisement since it would have become distinguishable to readers as a distinct text only after doing a double take and realizing that the layout deviated from expectations of how the page should appear.

Mary Goddard and Company were not the first printers to deploy the single-line advertisement that ran in the margin, but they added a new twist to the relatively few examples from other printers and other newspapers. Such single-line advertisements, when they did appear, spanned multiple columns across the top or bottom of the page. Just as they had previously played with other graphic design elements for the layout and format of advertising in the second half of 1766, Goddard and Company added their own innovation to the single-line advertisement printed in the margin.