What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

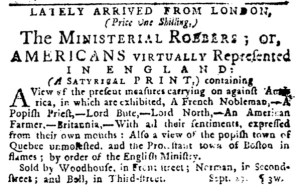

“AMERICANS VIRTUALLY Represented IN ENGLAND: (A SATYRICAL PRINT.)”

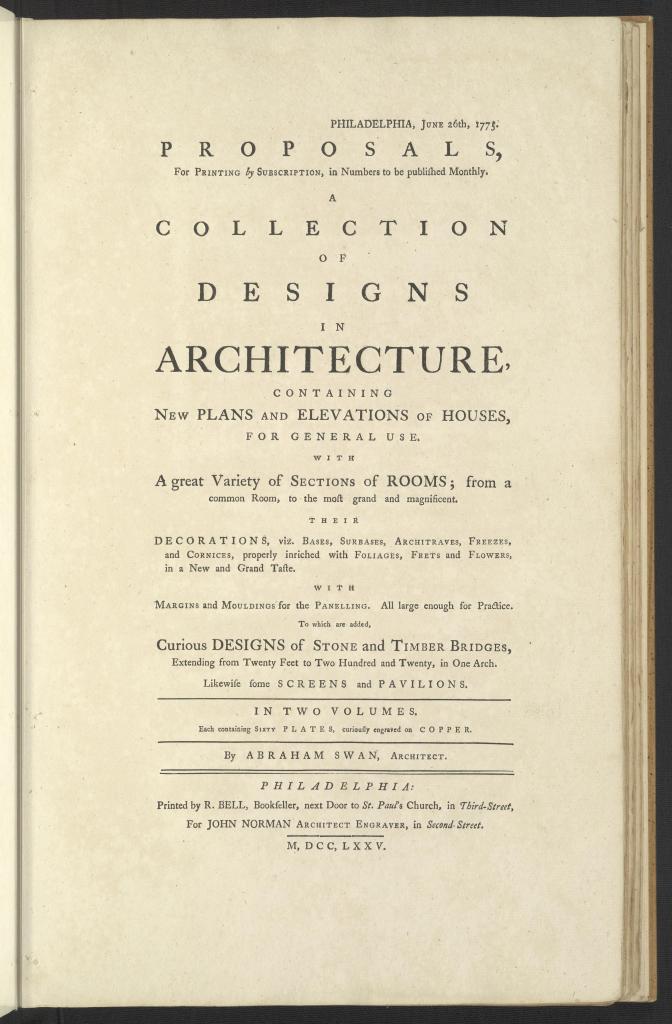

As the imperial crisis intensified and hostilities commenced in Massachusetts in the spring of 1775, American colonizers had supporters in London. In addition, some artists, engravers, and printers, whatever their own politics may have been, hoped to generate revenue by creating and publishing political cartoons that lambasted the British ministry for the abuses it perpetrated in the colonies. Some of those prints found their way to eager audiences on the other side of the Atlantic. In the fall of 1775, William Woodhouse, a bookseller and bookbinder, John Norman, an architect engraver building his reputation, and Robert Bell, the renowned bookseller and publisher, advertised a “SATYRICAL PRINT” that “LATELY ARRIVED FROM LONDON.”

The trio promoted “The MINISTERIAL ROBBERS; or, AMERICANS VIRTUALLY Represented IN ENGLAND,” echoing one of the complaints that colonizers made about being taxed by Parliament without having actual representatives serve in Parliament. Based on the description of the print in the advertisement, Woodhouse, Norman, and Bell stocked “Virtual Representation, 1775” or a variation of it. According to the newspaper notice, the image depicted a “View of the present measures carrying on against America, in which are exhibited, A French Nobleman,– A Popish Priest,– Lord Bute,– Lord North,– An American Farmer,– [and] Britannia.” For each character, “their sentiments, expressed from their own mouths,” appeared as well.

Lord Bute, the former prime minister who inaugurated the plan of regulating American commerce to pay debts incurred during the Seven Years War, appeared at the center of the image, aiming a blunderbuss at two American farmers. For his “sentiments,” he proclaimed, “Deliver your Property.” Lord North, the current prime minister, stood next to Bute, pointing at one of the farmers and exclaiming, “I Give you that man’s money for my use.” In turn, the first farmer stoutly declared, “I will not be Robbed.” The second expressed solidarity: “I shall be wounded with you.”

The advertisement indicated that the print also showed a “view of the popish town of Quebec unmolested, and the Protestant town of Boston in flames; by order of the English ministry.” Those parts of the political cartoon unfavorably compared the Quebec Act to the Coercive Acts (including the Boston Port Act and the Massachusetts Government Act), all passed by Parliament in 1774. The Quebec Act angered colonizers because it extended certain rights to Catholics in territory gained from the French at the end of the Seven Years War. In the print, the town of Quebec sat high atop its bluff, the flag of Great Britain prominently unfurled, in the upper left with the “French Nobleman” and “Popish Priest” in the foreground. The legend labeled it as “The French Roman Catholick Town of Quebeck.” The anti-Catholicism was palpable; the kneeling priest exclaiming “Te Deum” in Latin and holding a cross in one hand and a gallows in the other, playing on Protestant fears of the dangers they faced from their “Popish” enemies.

While Quebec appeared “unmolested” and even favored by Bute, North, and their allies in Parliament, the “English Protestant Town of Boston” appeared in the distance behind the American farmers in the upper right. The town was indeed on fire, a reference to the battles fought in the vicinity as well as a metaphor for the way Parliament treated the town to punish residents for the Boston Tea Party. As the advertisement indicated, Britannia, the personification of the empire, made an appearance in the print. She wore a blindfold and exclaimed, “I am Blinded.” She looked to be in motion, one foot at the edge of “The Pit Prepared for Others” and her next step surely causing her to fall into it. There seemed to be no saving Britannia as Bute and North harassed the American farmers and their French and Catholic “Accomplices” watched with satisfaction.

The description of the “SATYRICAL PRINT” in the Pennsylvania Journal merely previewed the levels of meaning contained within the image, yet in likely piqued the curiosity of colonizers who supported the American cause and worried about their own liberties as events continued to unfold in Boston. Such a powerful piece of propaganda supplemented newspaper reports, maps of the Battle of Bunker Hill, and political treatises circulating in the fall of 1775.