Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“NEGROES of different Qualifications.”

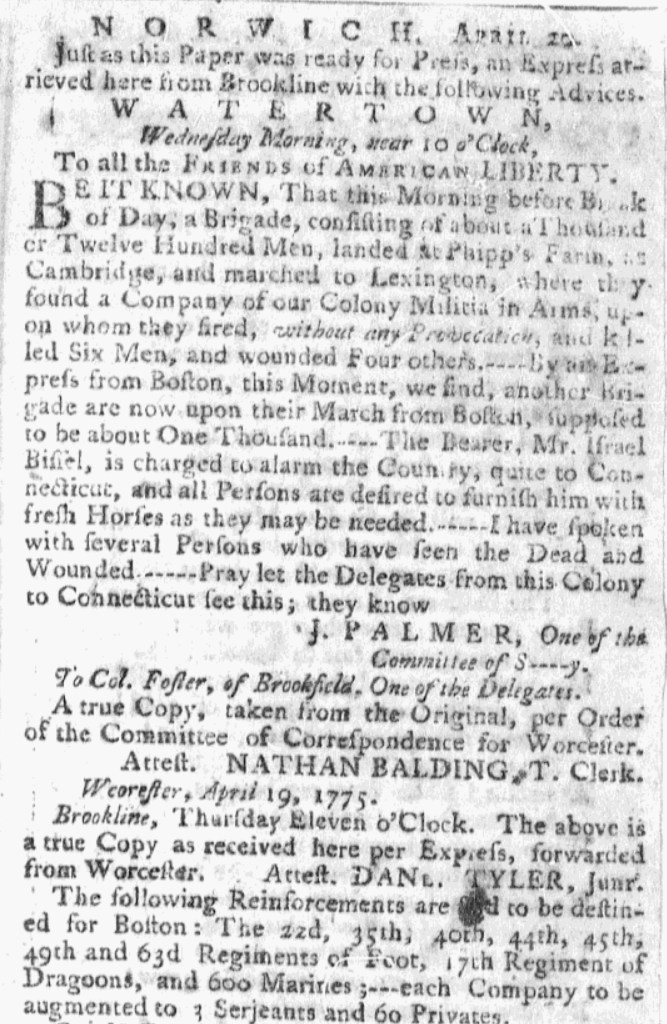

Charles Crouch usually published the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal on Tuesdays in 1775, distributing new issues on a different day than his competitors in Charleston. Peter Timothy delivered the South-Carolina Gazette on Mondays and Robert Wells and Son presented the South-Carolina and American General Gazette on Fridays. Yet as information about the battles at Lexington and Concord arrived in Charleston, Crouch published a two-page extraordinary issue on Friday, May 19. He had first broken the news in the May 9 edition, printing “alarming Intelligence” received via “the Brigantine, Industry, Captain Allen, who sailed the 25th [of April] from Salem.” Subsequent issues of both the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal and the South-Carolina and American Gazette carried news about Lexington and Concord. (A gap in extant issues between April 10 and May 29 prevents determining when the South-Carolina Gazette reported on those events.)

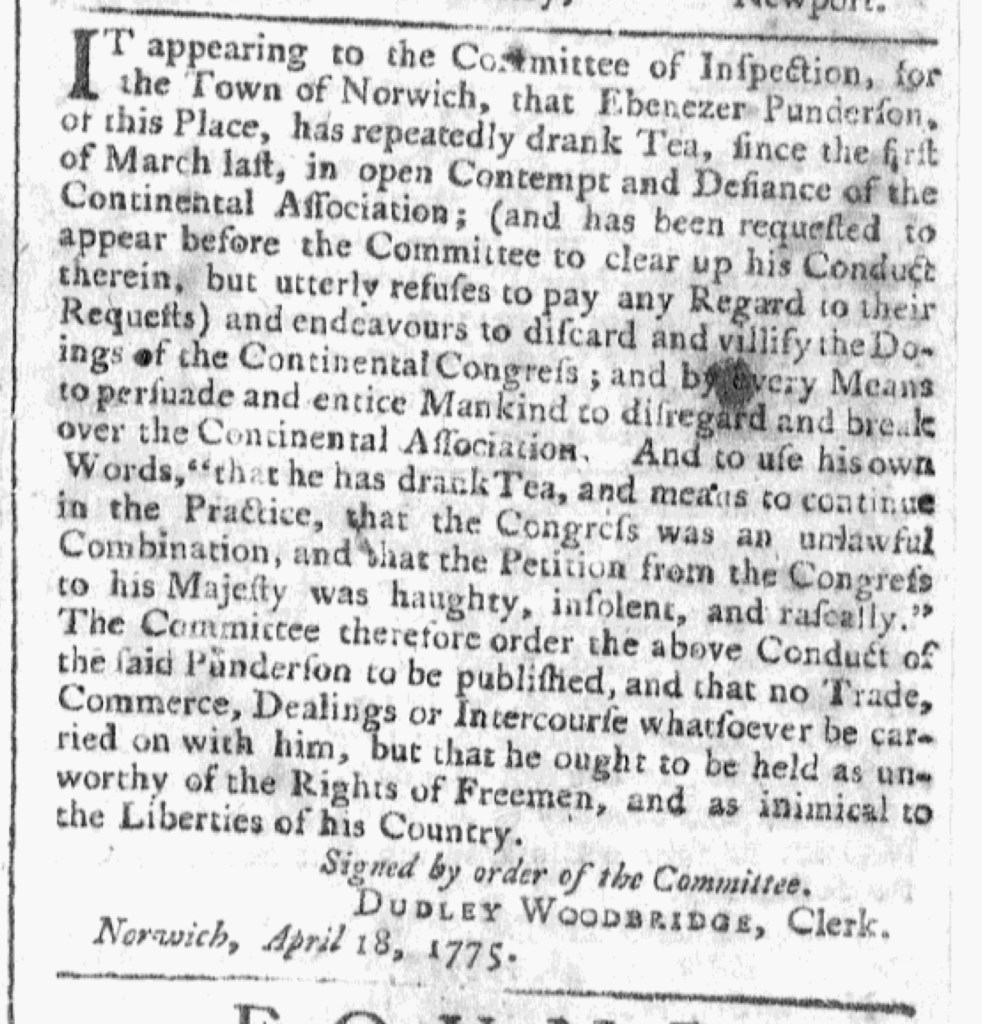

Many, perhaps most, readers likely heard that British regulars had engaged colonial militia outside of Boston before they read anything in newspapers. News and rumors spread via word of mouth more quickly than printers could set type, yet readers still clamored for coverage. After all, the public prints carried more details about what happened, though not all of them were always correct. Wells and Son printed the South-Carolina and American General Gazette as usual on Friday, May 19, carrying additional news about Lexington and Concord and the aftermath. Refusing to be scooped, Crouch published his extraordinary issue on the same day. He specified that the “particulars respecting the Engagement at Lexington, are copied from the Newport Mercury.”

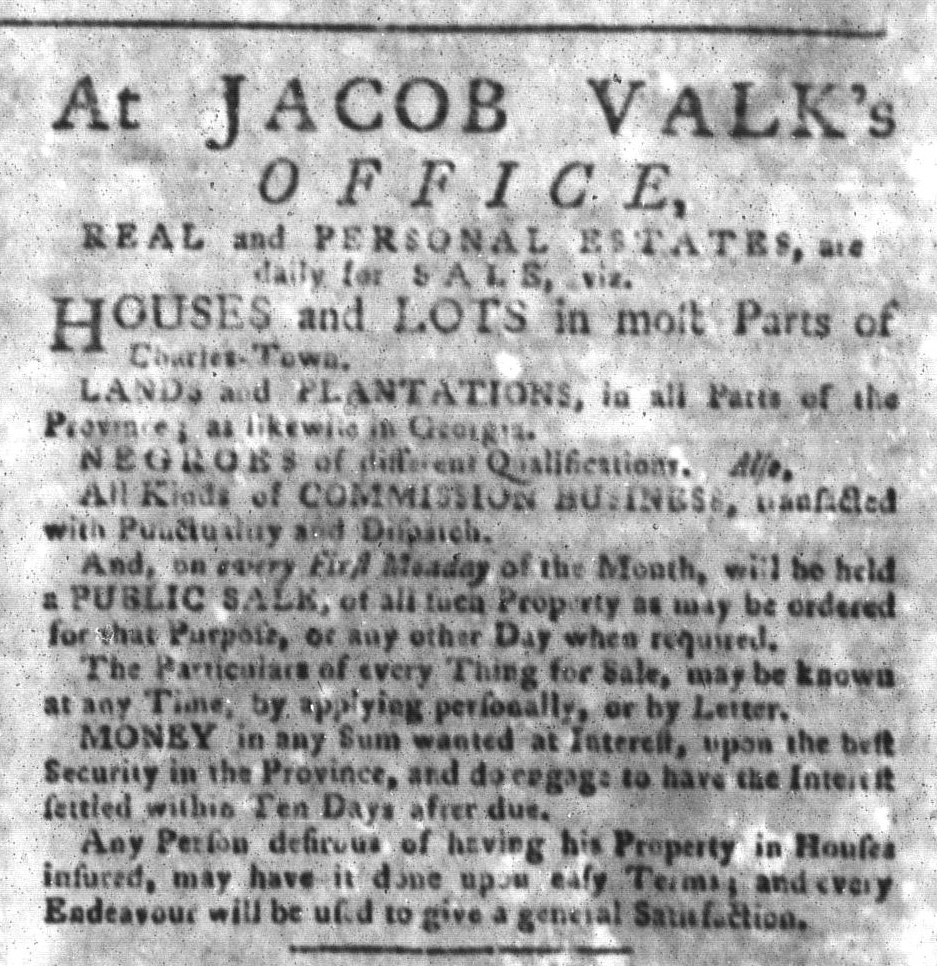

Even as Crouch provided more news for subscribers and the public, he disseminated even more advertisements. News accounted for only one-quarter of the contents of the May 19 extraordinary issue, with advertisements filling three-quarters of the space. Those notices included three from Jacob Valk, a broker, looking to facilitate the sales of “ONE of the compleatest WAITING-MEN in the Province,” “Some valuable PLANTATION NEGROES,” and “NEGROES of different Qualifications” at his office. In another advertisement, William Stitt described Lydia and Phebe, enslaved women who liberated themselves by running away, and offered rewards for their capture and return to bondage. In yet another, the warden of Charleston’s workhouse described nearly a dozen Black men and women, all of them fugitives seeking freedom, imprisoned there, alerting their enslavers to claim them, pay their expenses, and take them away. As readers learned more about acts of tyranny and resistance underway in Massachusetts, they also encountered various sorts of advertisements designed to perpetuate the enslavement of Black men and women. The early American press simultaneously served multiple purposes, regularly featuring a juxtaposition of liberty and slavery that readers conveniently compartmentalized.