What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“To the surprise of myself and neighbours, found myself recovered to health.”

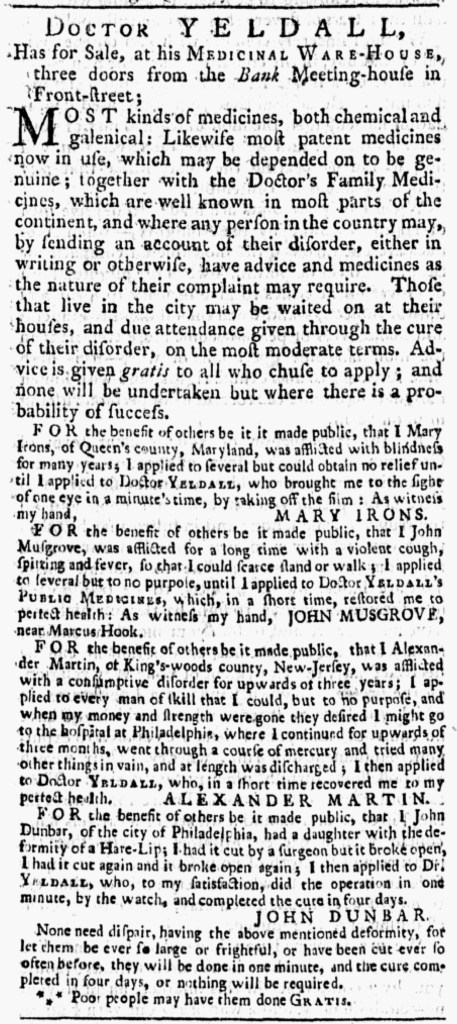

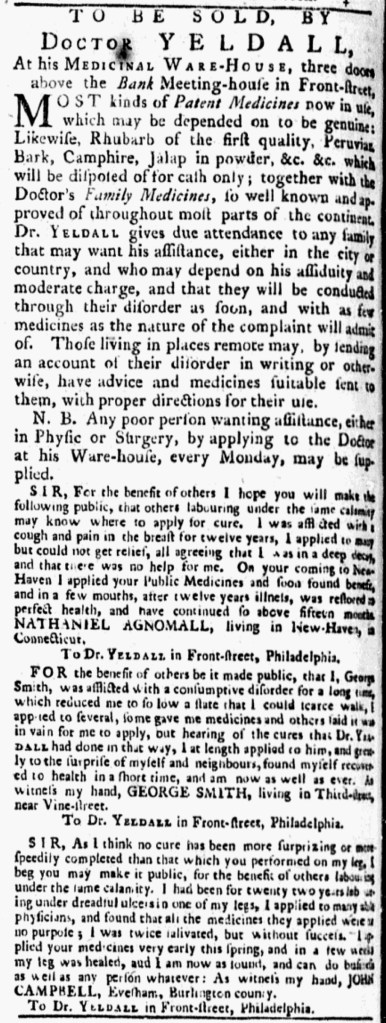

Doctor Yeldall apparently believed that testimonials worked. In June 1775, he published an advertisement that included several testimonials from his patients. Three months later, he once again promoted his “MEDICINAL WARE-HOUSE’ in Philadelphia with an advertisement that featured three new testimonials. The notice gave the impression that the doctor had not solicited them, but instead merely published letters addressed “To Dr. YELDALL in Front-Street, Philadelphia” at the request of those who sent them. “For the benefit of others I hope you will make the following public,” Nathan Agnomall’s testimonial began. Similarly, John Campbell, who had suffered “dreadful ulcers in one of my leges,” implored the doctor: “I beg you may make it public, for the benefit of others labouring under the same calamity” that Yeldall’s medicines healed leg.

In his preamble to the testimonials, Yeldall described his “Doctor’s Family Medicines” as “so well known and approved of throughout most parts of the continent.” Two of the testimonials did indeed come from beyond Philadelphia. Campell listed his address as “Eversham, Burlington county,” in New Jersey, while Agnomall stated that he was “living in New-Haven, in Connecticut.” The third testimonial, however, came from a resident of Philadelphia, George Smith, “living in Third-street, near Vine-street.” Skeptics in that city could question the veracity of letters that supposedly arrived from other colonies, but they might know Smith or could seek him out to confirm what they saw printed in the newspaper advertisement. Smith’s letter even revealed that he had been cured of a “consumptive disorder” and “to the surprise of myself and neighbours, found myself recovered to health.” Many residents of Philadelphia living in Smith’s neighborhood could also testify to the efficacy of the Yeldall’s medicines, at least that was the inference in Smith’s letter. Unlikely to attempt to track down Smith or interview any of his neighbors, prospective patients who had not found relief through any other means may have found this testimonial convincing enough to give Yeldall’s medicines a chance. Even if they had doubts, the details in Smith’s letter gave them hope by encouraging them to believe something that was likely too good to be true.